In This Article

In May 2017, Frank Massabki and his fiancée, Jennifer, traveled to Mexico City to scout locations for their upcoming wedding. An hour after renting a car in the city, they were rear-ended by another vehicle. The couple told Inside Edition that they stepped out to inspect the damage, but were approached by several men with guns who threw them into the backseat and drove them to a location they didn’t recognize. The kidnappers bound their wrists with shoelaces, blindfolded them, and said they planned to demand a ransom. The men then attempted to sexually assault Jennifer, but she fought back, receiving a punch to the face that broke her nose. During this struggle, Frank managed to escape from his crude restraints and ran to call for help. Realizing they had lost control, the kidnappers fled, and the couple were able to return home to the United States.

As a result of countless melodramatic Hollywood depictions, kidnapping may seem like a distant threat — the sort of thing that only happens if you’re a secret agent, millionaire businessman, or key witness in a mafia murder trial. But the unfortunate reality is that it does happen to ordinary people like the Massabkis, especially in impoverished countries where ruthless criminals and corrupt officials view foreigners as high-value targets. And if these individuals can’t get what they want, most won’t hesitate to resort to torture, rape, or murder.

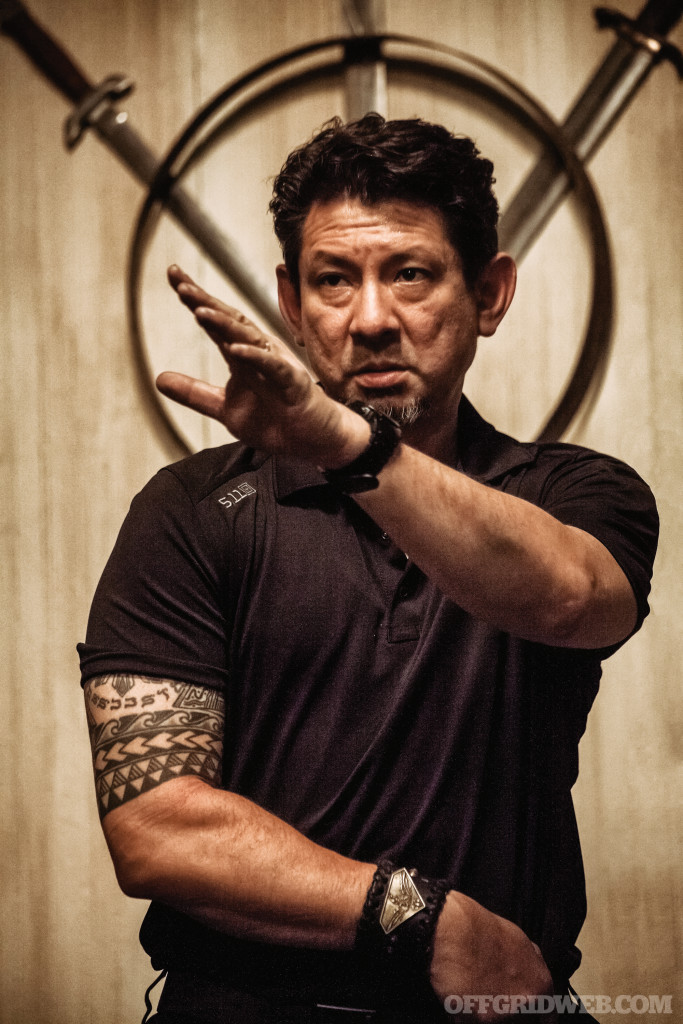

Ed’s Manifesto: Counter-Custody Training

Ed Calderon, who you may recognize from our Survivalist Spotlight interview in Issue 25, has forged a career as a specific type of survival instructor. Based on firsthand experience with the cartels during his time as a Mexican law enforcement officer, Calderon has developed an in-depth curriculum that teaches students how to avoid abduction and escape captivity. These courses are more than just academic theory — they place students in simulated kidnapping scenarios, and give each individual a jarring glimpse of the physical and psychological trauma that can ensue.

We recently attended one of Ed’s two-day counter-custody courses, and learned several skills that can help you turn the tables on kidnappers and increase your odds of making it home alive. These principles can help you avoid unnecessary attention from would-be attackers, and develop the resolve to escape life-threatening illegal imprisonment.

1. Know Thy Enemy

Situational awareness and threat identification are cornerstones of self-defense, whether you’re concerned about theft, assault, or abduction. Given Ed’s experience in Mexico, the first portion of the class was dedicated to spotting cartel members and their associates. If you think that these individuals only exist south of the border, he’ll be the first to tell you that you’re sorely mistaken — demand for street drugs and human trafficking has maintained a healthy network throughout the United States.

There are many physical cues that can help you identify someone who’s accustomed to violence. A crooked nose, cauliflower ears, and scarring on the knuckles are clear signs of physical brawls; a callus on the middle finger of the dominant hand speaks of many hours rubbing against the trigger guard of a weapon. Muscular physical build isn’t necessarily an indicator, as many hardened criminals are overweight or out of shape. Tattoos are also hit or miss, as high-level criminals know better than to brand themselves with identifying marks. In modern cartel circles, streetwear fashion is increasingly popular — skinny jeans and high-end sneakers have replaced stereotypical cowboy apparel and snakeskin boots.

Above: Students were blindfolded, doused in aerosol body spray, and exposed to continuous loud music as a form of sensory deprivation.

Ed says cartel members are often “armed to the teeth” with weapons ranging from full-auto-converted civilian ARs and AKs to grenades and belt-fed machine guns. Unsurprisingly, gun laws in the U.S. and Mexico haven’t prevented them from acquiring these weapons. Fighting tactics and communications are generally primitive, but this is changing as new-generation cartel members realize the value of thermal optics, drones, and other modern resources. Restraints often consist of surplus or off-brand handcuffs, rope, duct tape, and commercial zip ties or purpose-built zip cuffs. These basic materials are combined in devious variations — for example, tethering cuffs to a belt loop to restrict arm movement.

Above: You may have seen videos depicting how to break out of zip ties using a swift downward motion of the arms. Cartel members saw them too, and developed these “vampire” cuffs to cut open the wrists of captives who try to break free.

The ability to piece together these clues and understand the threat early can provide time to defend against it instead of being blindsided. Knowing your enemy also lets you know what to expect if you’re taken captive.

2. Never Go Without Tools

In any survival situation, tools provide a tremendous advantage, and this is especially true in captivity. With proper training, items such as handcuff keys, shims, a Kevlar cord saw, and a sharp blade can help you escape most restraints. However, getting these tools through a rudimentary pat down — much less a thorough search — isn’t an easy task.

Above: Handcuffs, scraps of cord, and duct tape were combined to make multi-stage restraints that selectively restricted movement.

During the counter-custody class, students practiced escaping handcuffs in various positions using cuff keys and shims. We were then tasked with concealing these tools to make it through a head-to-toe search. This process led to an acronym Ed Calderon refers to as ACPN:

Access: Can you get to the tool while wearing cuffs? What if it’s behind your back? What if you’re blindfolded and lying face-down? The waistline and ankles are generally easiest to access while restrained.

Concealment: Can the tool be hidden from a visual inspection, pat-down, metal detector, or even a strip search? This must be balanced with accessibility, since deep-concealed items may not be reachable when you need them.

Above: Ed Calderon showed us a shim retained in the stitching on the inside of his belt loop, and a hidden cuff key slipped into the waistband of his jeans.

Permanence: Will the item stay with you in a SHTF situation? For example, your fancy SERE kit paracord bracelet will almost certainly be removed by kidnappers, so storing critical items there is unwise.

Narrative: If your tools are found, what do they say about you? A concealed ceramic knife may lead captors to think you’re a spy or assassin; a set of lockpicks could be considered burglary tools. Also consider disposability and traceability — a dollar store paring knife is superior to an expensive dagger engraved with a serial number.

3. Prepare to Improvise

In many cases, carrying purpose-built tools isn’t an option. Perhaps the search is extremely thorough, or the consequences of getting caught are too severe to risk carrying them. In these cases, you’ll have to improvise once you’ve cleared security.

Above: Students were told to conceal escape tools for each scenario, and were then thoroughly searched before being restrained. In the final test, pants and shoes were also confiscated.

One key point stuck with us: You don’t have to carry what you need — you just have to get the materials to make what you need. Knives might be banned where you’re going, but there are countless unrestricted items you can carry to craft a deadly shiv in a few minutes. A toothbrush can be sharpened into a point on sandpaper or concrete; rubbing a clear plastic BIC pen rapidly against carpet makes a syringe-like “ventilator” weapon in less than 10 seconds. A basic metal hair clip or the tweezers from a Swiss Army Knife serve as surprisingly effective handcuff shims.

Ed describes this mindset as “software over hardware.” Despite the undeniable value of tools, knowledge and resourcefulness are far more valuable.

Above: Students crafted concealable shivs from wood, plastic, and metal. One particularly vicious weapon (at bottom right) even included breakaway cactus spines attached with electrical tape.

4. The Clock is Ticking

In general, captivity situations don’t get easier as time passes. They get more difficult and more dangerous. Minutes after you’re taken prisoner, you may still have your shoes, clothes, and concealed tools. After a few hours or days, it’s likely that these items will be found and stripped away. The last thing you want is to end up naked, blindfolded, and hogtied. On top of this, abuse and malnutrition will gradually weaken your body and dull your senses, or your assailants may decide you’re a liability and execute you. Calderon tells us many of those abducted by the cartels are never found. They’re killed, the flesh is melted in caustic soda, and the bones are dumped in mass graves.

Above: A length of braided Kevlar cord (sold in bulk as competition kite string) can easily be woven through the waistband or inseam. Looping it around each foot and moving in a pedaling motion can cut through many restraints in seconds.

The point is simple: The best time to escape is immediately. Look for the first possible opportunity and seize it like your life depends on it — it probably does.

5. Fight for Your Life

Escape isn’t always as simple as breaking your restraints and sneaking past a distracted guard. In many cases, you may have to fight your way through an armed individual to create an opening. In these cases, you’ll need to use the element of surprise and attack with deadly force.

Since it’s unlikely you’ll have access to a gun, knife, or any other purpose-built weapon in these scenarios, start thinking like a prisoner — make a shiv. A slim and solid piercing weapon that reaches the length of your outstretched thumb is enough to kill. Repeated “sewing machine” strikes with a hammer-fist motion are powerful, especially when targeting vital areas like the subclavian artery (behind the collarbone) or the heart (two finger widths below the left nipple). Even simple items such as a screwdriver or sharp piece of plastic can be deadly in this capacity, and little to no experience is needed to wield them. Calderon reinforced this point by showing the class several graphic LiveLeak videos of stabbing incidents (here’s one fatal example), and letting students watch as the victims bled out in minutes. These unfortunate individuals are often fatally wounded before they even realize they’re being stabbed.

When you’re facing captivity, torture, or worse, fighting fair is off the table. Using deadly force with an improvised weapon may be your only way to survive.

Escaping Handcuffs

Many people assume handcuffs are only used by law enforcement officers on criminals — or perhaps used in the bedroom if you’re feeling adventurous. Unfortunately, criminals have firsthand experience with the effectiveness of these devices, and will have no qualms about using them to illegally restrain their captives. Knowing how to break free from a pair of handcuffs is a valuable skill, since doing so may be the last thing your captors expect.

1. A cuff key (left) and shim (right) from SerePick provide two effective means of escaping most standard handcuffs. Calderon recommends a metal key, since plastic keys are easy to snap and may generate the wrong narrative if found by authorities.

2. The shim is inserted into the locking mechanism atop the ratcheting teeth.

3. While applying downward and inward pressure to the shim, the cuffs are tightened by at least two clicks to force the shim deeper into the mechanism.

4. Once the shim is fully inserted, holding it in place while rolling the wrist will cause the cuff to slide open.

5. The open cuff can now be used as an improvised impact weapon.

“The Prison Wallet”

Where do you hide tools when there’s nowhere left to hide? The answer is an unpleasant but necessary option that has developed a reputation among prison inmates. No matter what nickname you use or how many jokes you make about this smelly stash spot, it provides a last-resort means of smuggling essential escape tools past a strip-search. If your life depends on it, you won’t be laughing.

Ed showed us a few examples of caches that are effective for this purpose, including a metal lip balm tube from the 1960s, a WWII-era threaded metal capsule, and a custom tube made out of bamboo. These containers are small enough to be retrieved safely, but large enough to carry keys, shims, lockpicks, or even a blade. Plastic and other fragile materials should be avoided since they may break open in transit, leading to a very awkward trip to the emergency room.

Conclusion

For many of us, the likelihood of being kidnapped or held prisoner is relatively low. But as any prepared individual should know, we must weigh the likelihood of an event with the severity of its consequences. These scenarios are some of the most dangerous you could ever face, since they place you almost entirely at the mercy of captors who are likely to be merciless. But by leveraging these five principles, you’ll be better prepared for captivity and give yourself a fighting chance at becoming the one who got away.

Sources:

- Ed Calderon – edsmanifesto.com

- SerePick – serepick.com

More From Issue 29

Don’t miss essential survival insights—sign up for Recoil Offgrid’s free newsletter today!

- Review: Crawford Survival Staff

- Parental Preps Issue 29

- Understanding Energy Drinks & Their Ingredients

- Book Review: “Gray Man: Camouflage For Crowds, Cities, and Civil Crisis”

- Vanishing Act: 5 Tips for Surviving a Kidnapping

- Take Your Best Shot: Prepper’s Slingshot Roundup

- Doug Marcaida Spotlight – Into the Fire

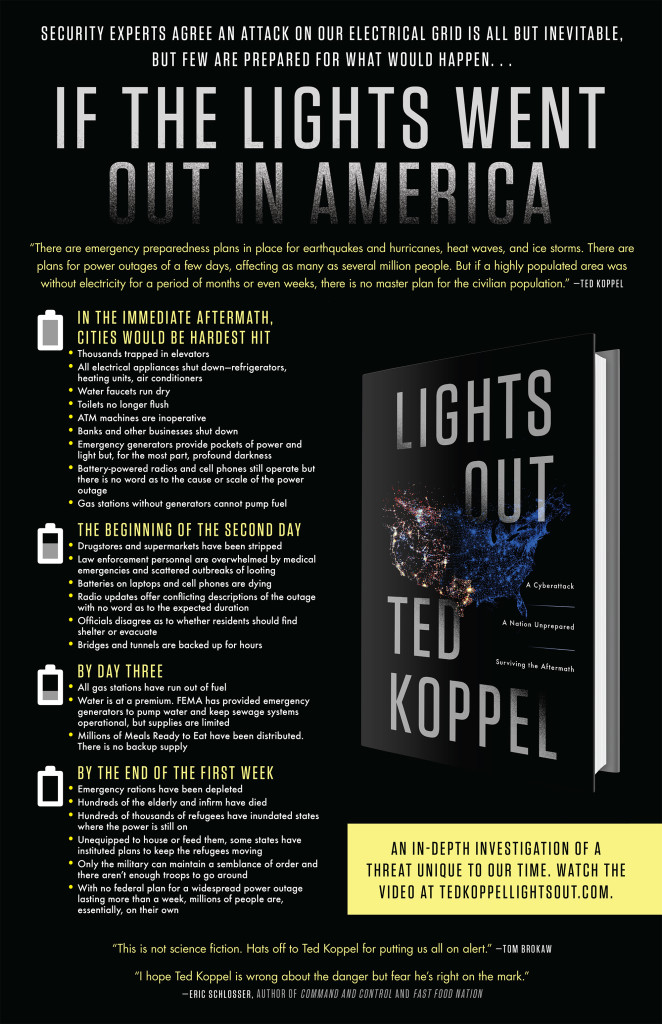

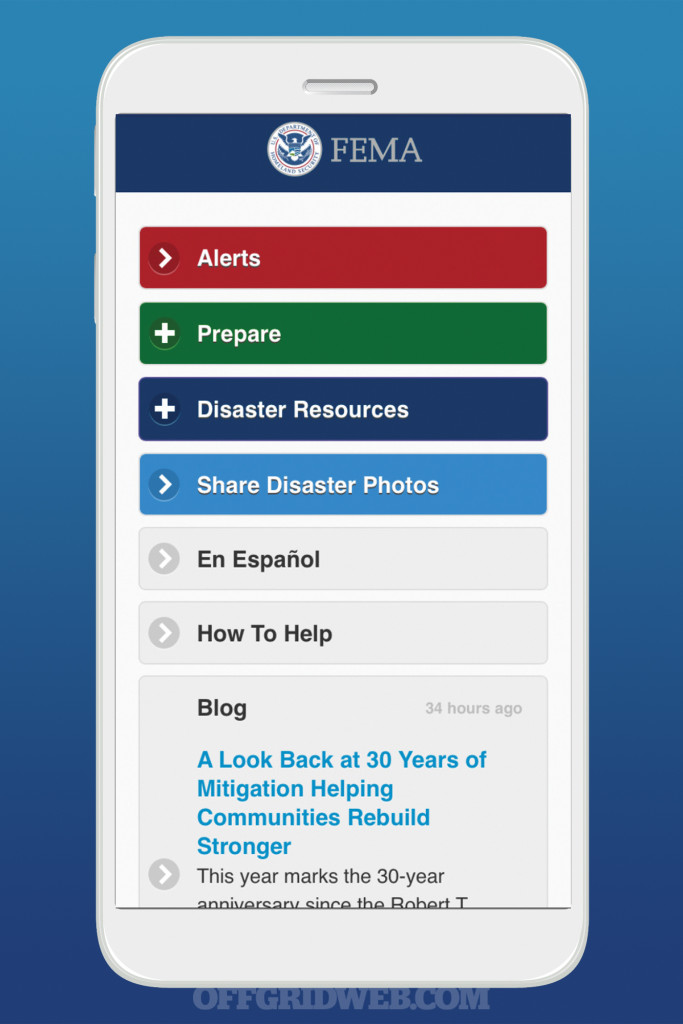

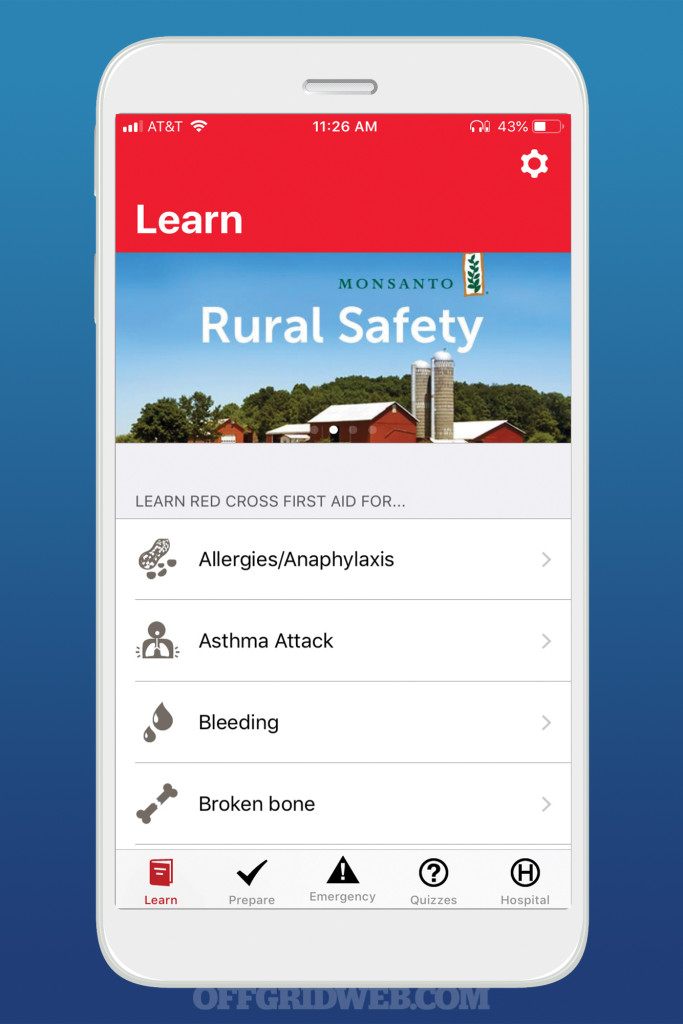

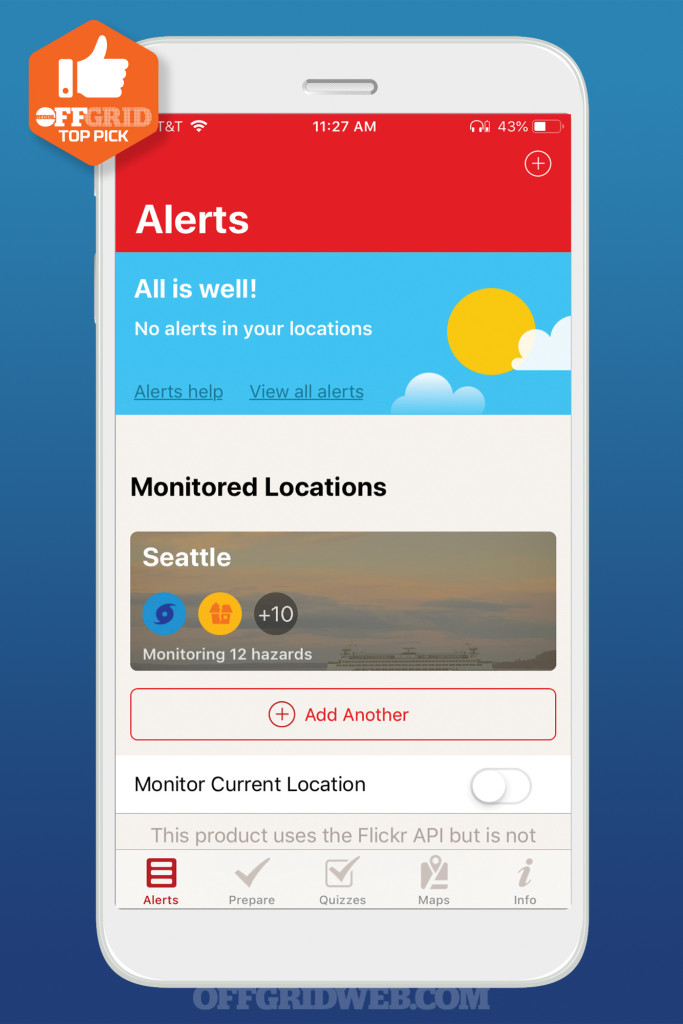

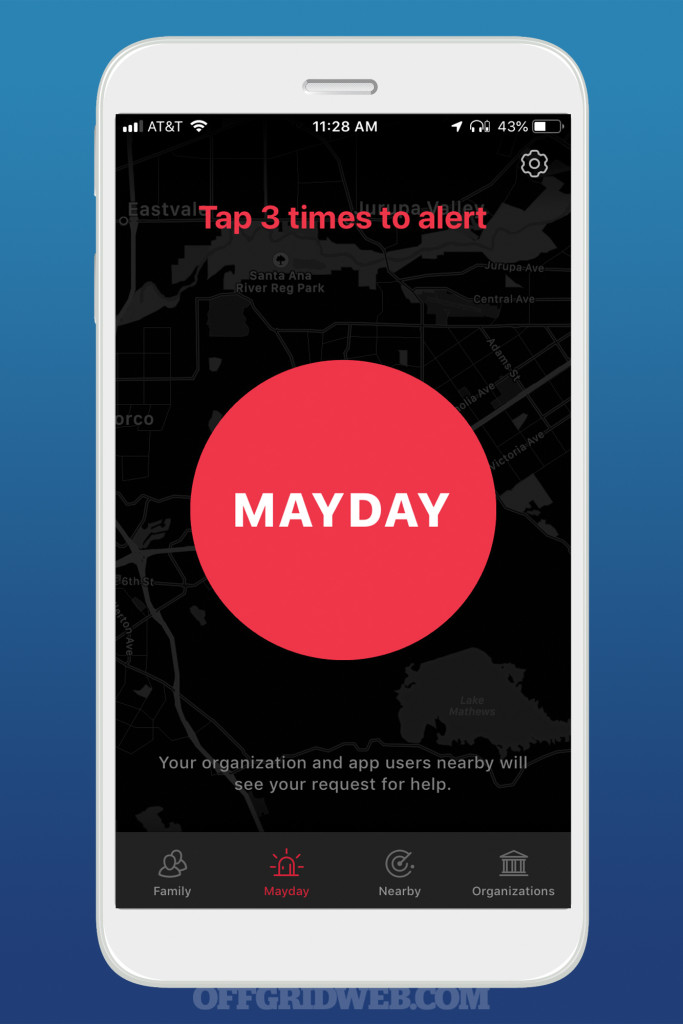

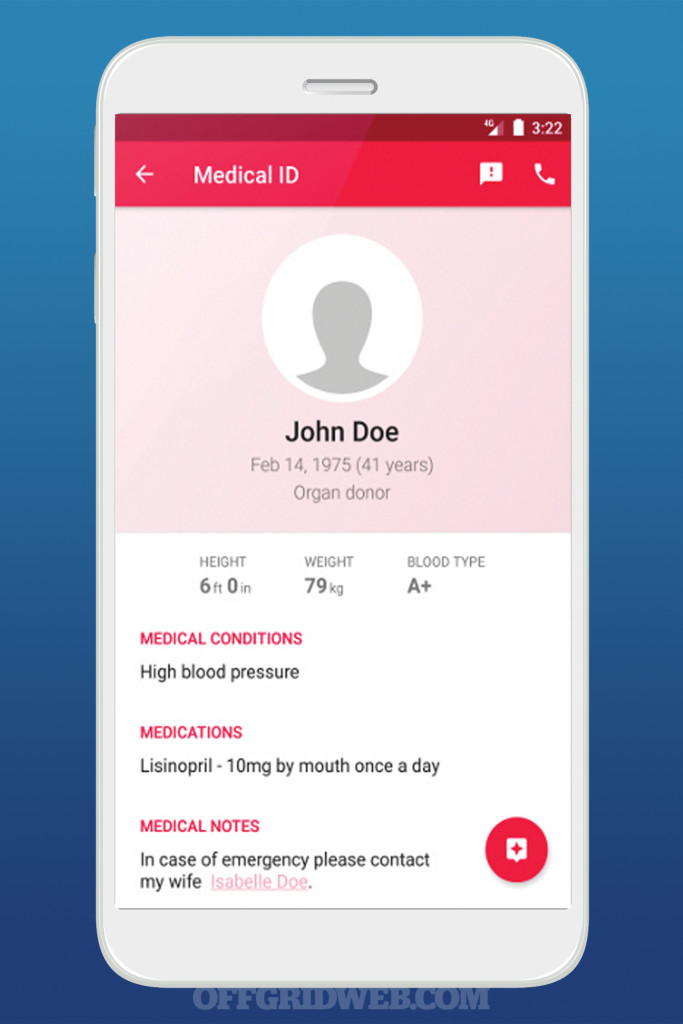

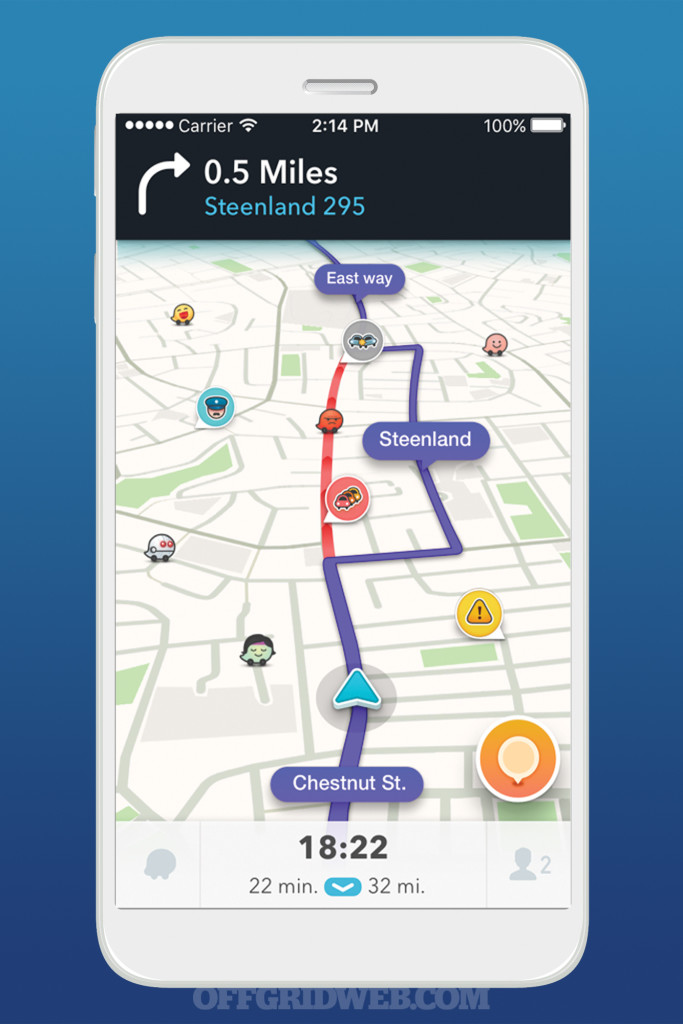

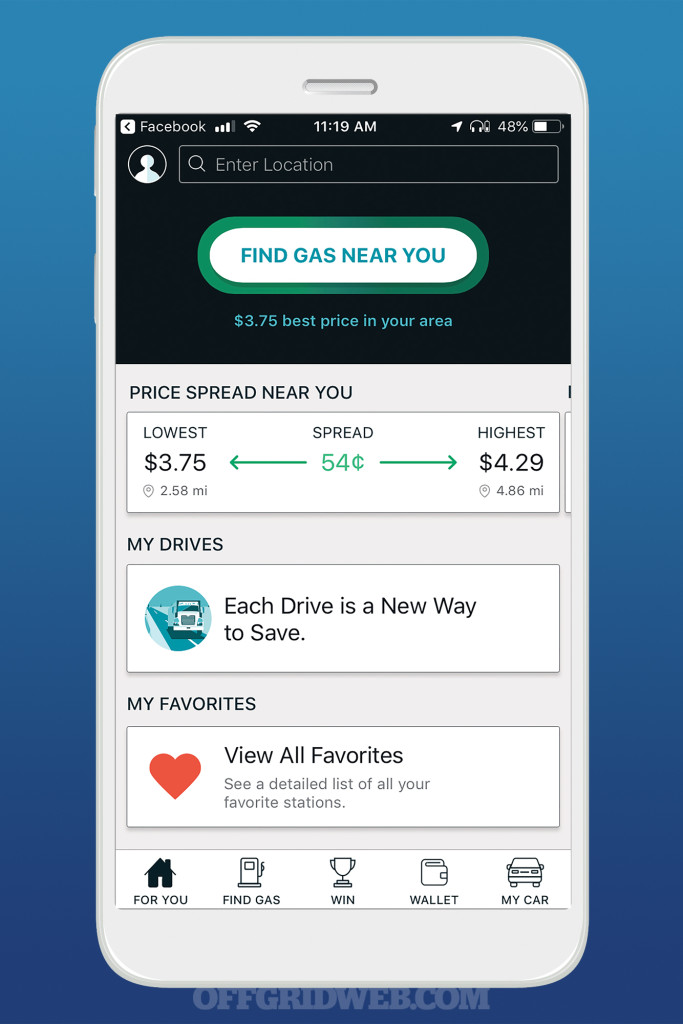

- Review: 10 Emergency Apps for iOS and Android

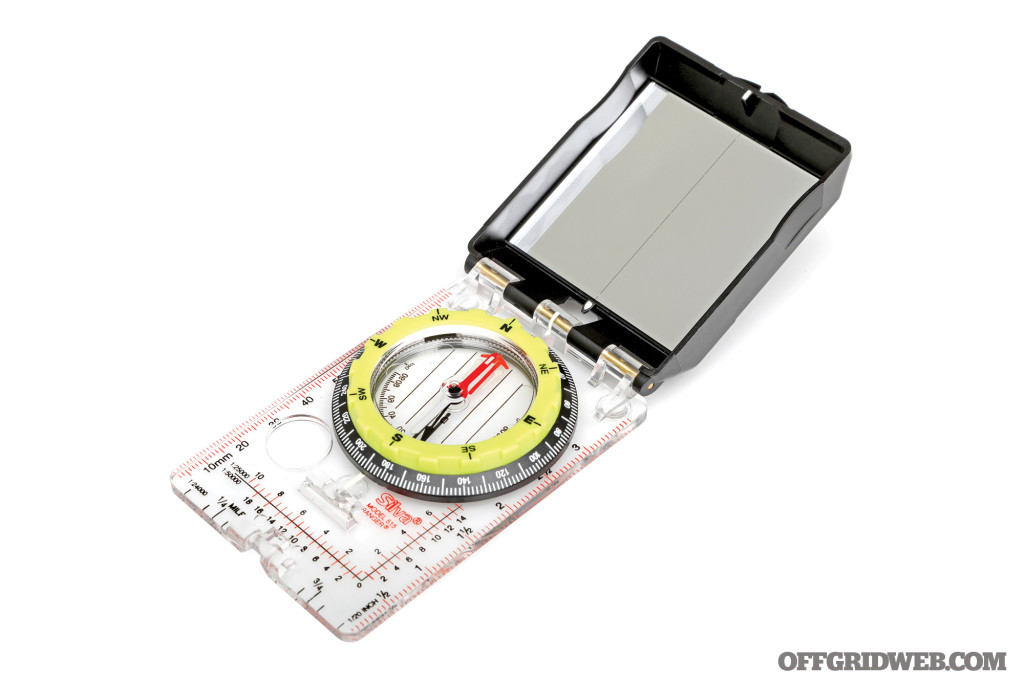

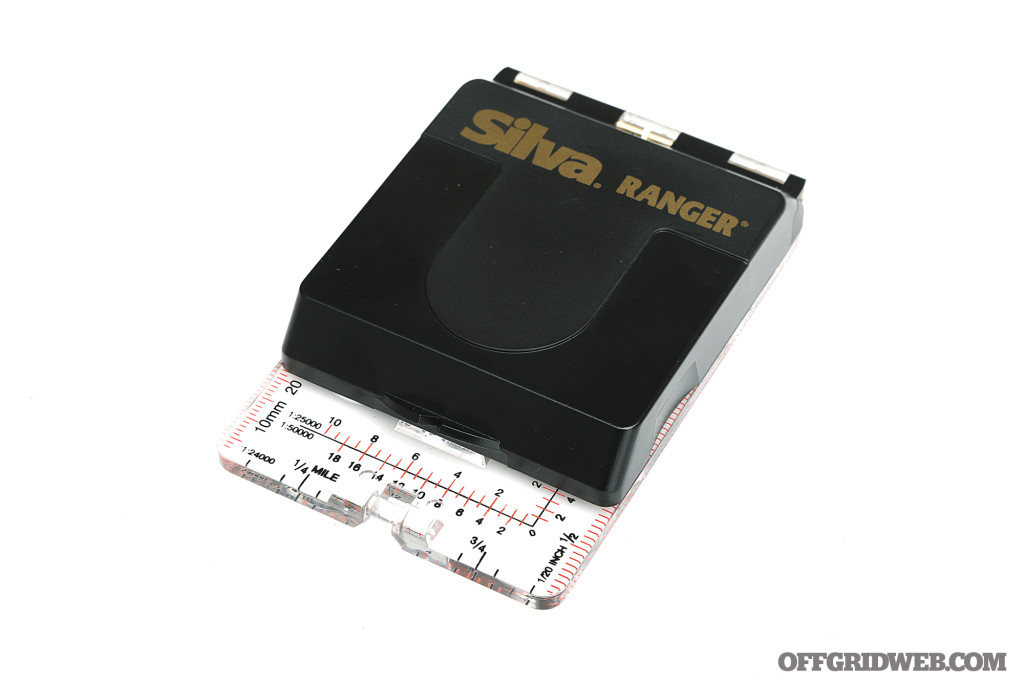

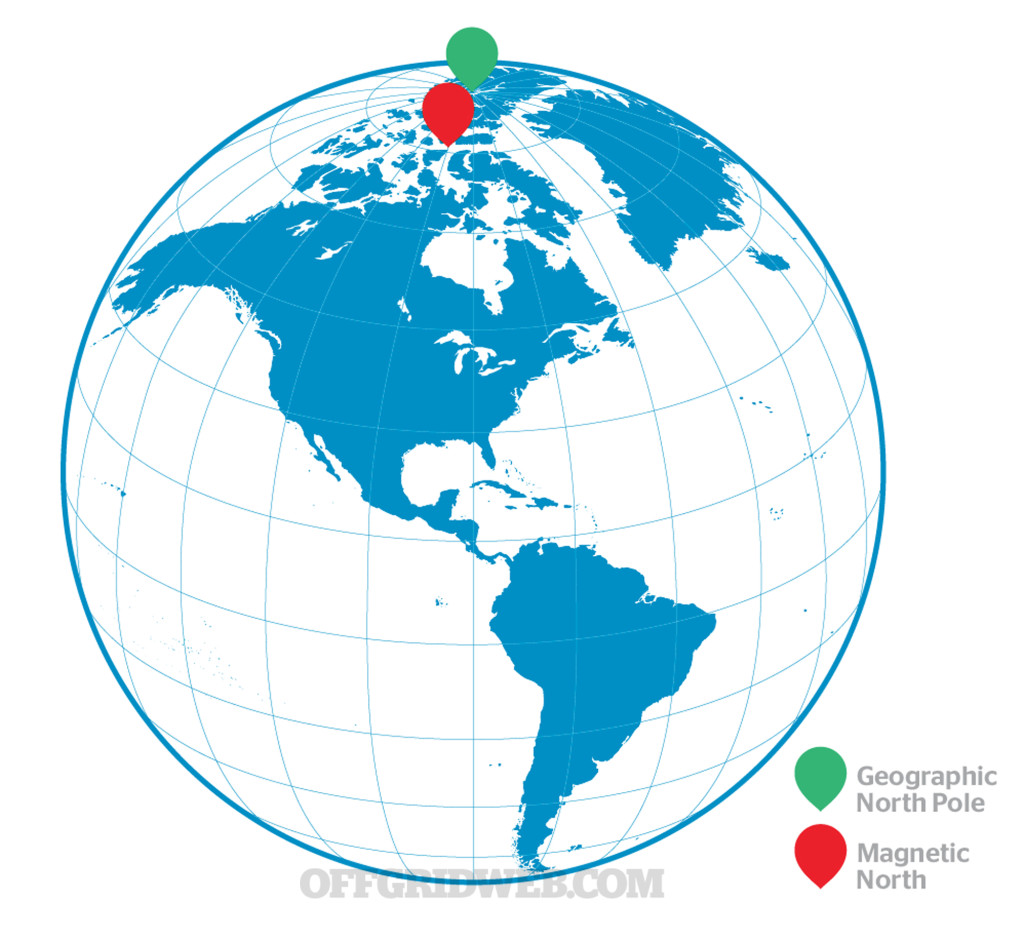

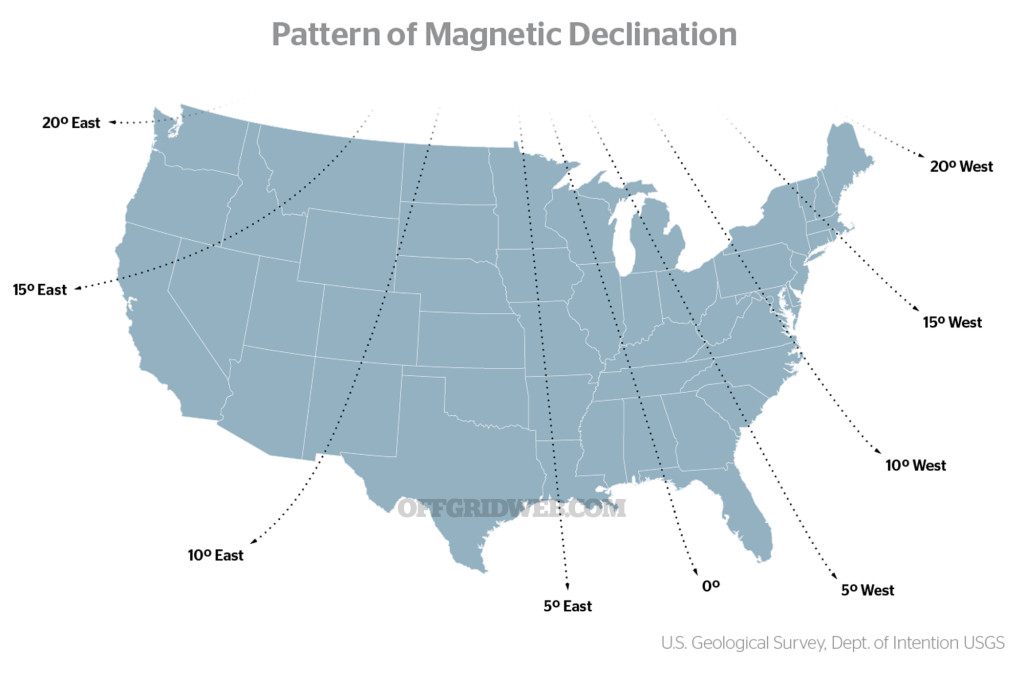

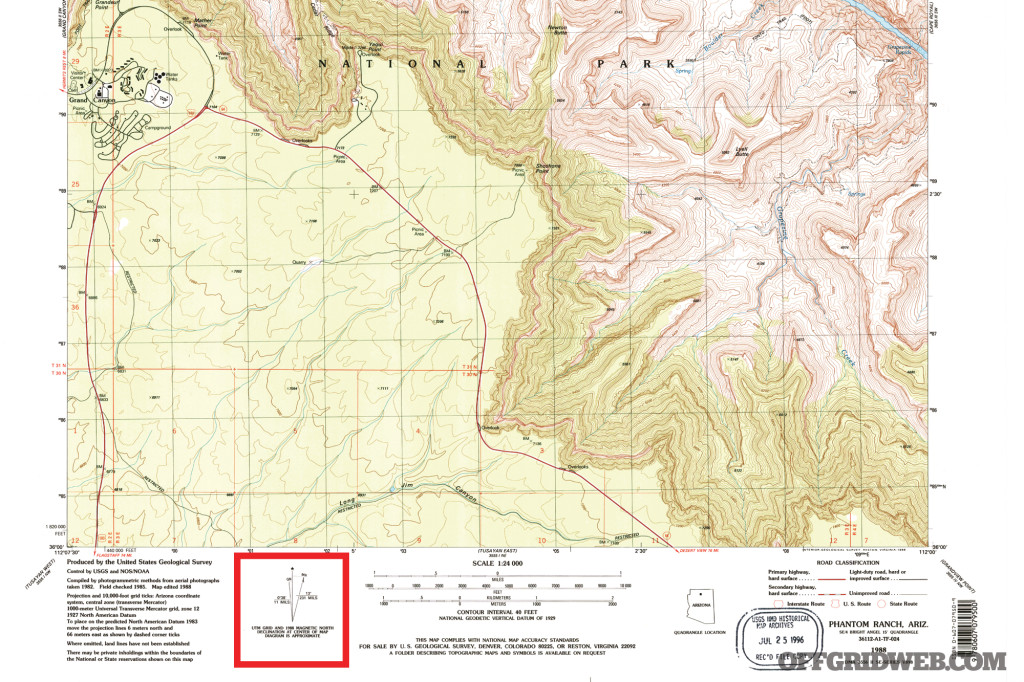

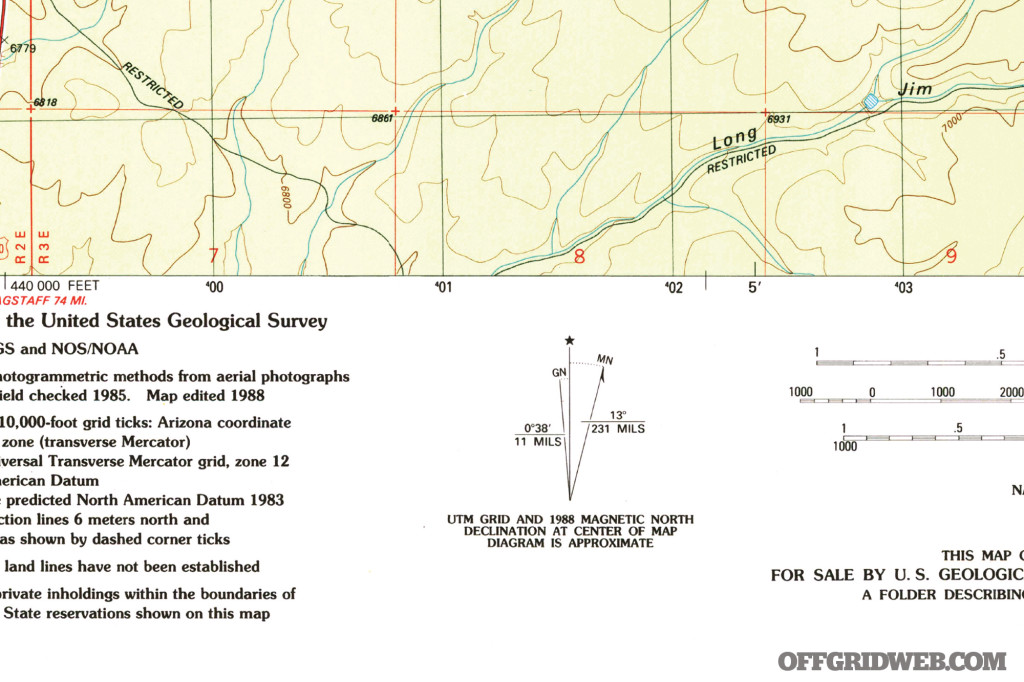

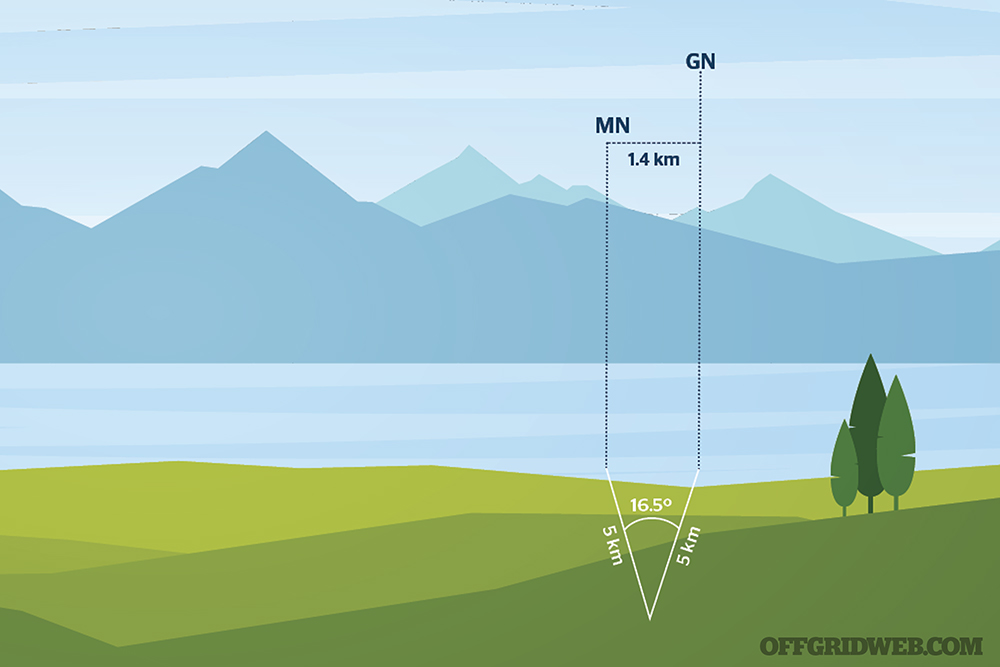

- Point the Way: Survival Compass Buyer’s Guide

- Old-School Navigation: How to Use a Map and Compass

- Review: Veritas Tactical VT-16 5.56mm AR Pistol

- Disaster Insurance: Hedging Your Bets for SHTF

- What If Your Flight is Hijacked by Terrorists?

- Pocket Preps: Wallets

- Issue 29 Gear Up

Read articles from the next issue of Recoil Offgrid: Issue 30

Read articles from the previous issue of Recoil Offgrid: Issue 28

Check out our other publications on the web: Recoil | Gun Digest | Blade | RecoilTV | RECOILtv (YouTube)

Editor’s Note: This article has been modified from its original version for the web.