The public is often led to believe that human trafficking only happens in other countries. Theresa Flores is living proof that it’s been happening in the United States for a long time. It’s often linked to some very sinister people in positions of power, and no one’s immune to it. She was trafficked as a young girl in the Michigan suburbs, before the internet existed and names like Jeffrey Epstein were in the 6 o’clock news. She escaped her nightmare and not only detailed what she endured in her book, The Slave Across the Street, but became a respected authority on the topic and relentlessly tours the country working with other survivors to fight this perverse form of conscription.

In Theresa’s words, human trafficking is a “silent epidemic.” It’s orchestrated by highly sophisticated criminals who use intimidation, extortion, bribery, and violence to continue its onslaught. Various businesses are fronts for it. The dark web is a marketplace for victims being bought and sold. Social media, apps, interactive video games, and hangouts where children congregate draw predators out of the woodwork looking for victims to exploit. Their future may include sexual and emotional abuse, beatings, organ harvesting, forced labor, torture, or murder.

We spoke with Theresa Flores about her experience, what the public needs to know to protect themselves and their kids, and how her organization, SOAP (Save Our Adolescents from Prostitution) Project, raises awareness. The question then becomes, will you dismiss her personal account as an isolated incident that could never happen to your loved ones, or will you be convinced that it deserves more coverage than other hot topics on the evening news ever did? After reading her story, and our feature on this topic elsewhere in this issue, we hope you’ll agree that no child should have to suffer through this kind of sordid opportunism.

After hearing Flores speak, other survivors often get the courage to confide in her and seek advice.

RECOIL OFFGRID: Where’d you grow up?

Theresa Flores: All over the place. That was probably one of the things that made me more vulnerable than the average kid — we moved every two years. I was born in Ohio and my dad got a job with General Electric, so we moved all over Ohio, Indiana, and Michigan.

Tell us about how your experience being trafficked began.

TF: In the middle of my freshman year in high school, we moved to a new area that was outside of a big city. It was very different for me and fast-paced. A boy from school started to notice me and asked if I wanted to go out, but I wasn’t old enough to date. For about six months he groomed me, but as a kid you think they’re courting you because you’re getting a lot of compliments. One afternoon, he asked me if I wanted a ride home from school, but he didn’t take me home. Instead, we went to his house. I was drugged and raped. After that, he and the group that he was in, which was like a middle-class, Middle Eastern gang, ended up blackmailing me with photos they took while I was drugged and selling me to men for the next two years.

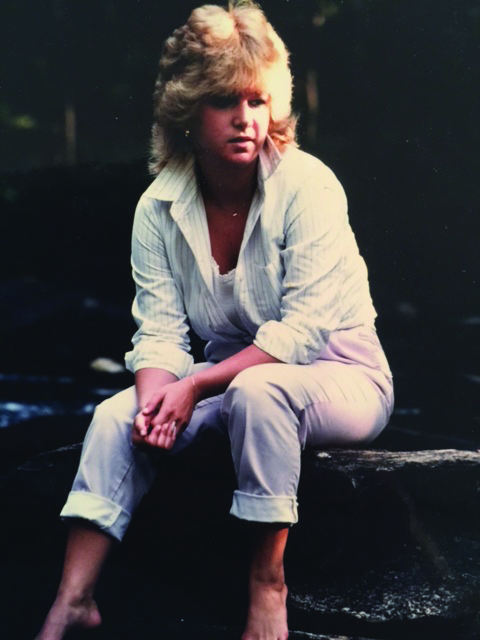

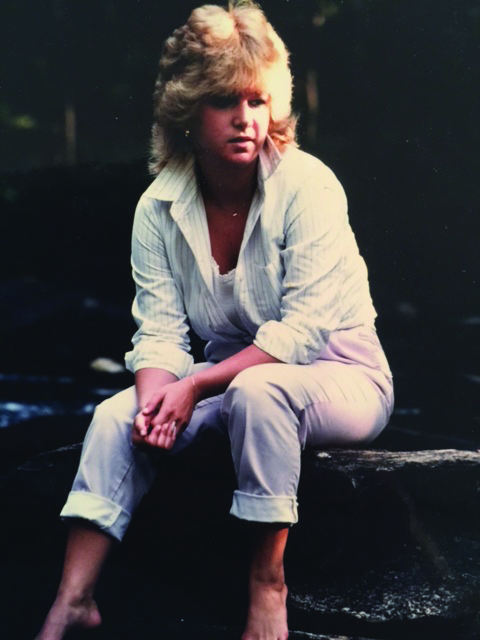

Stratford, Connecticut, 1983. After escaping, she struggled to heal during her senior year of high school.

What year was this and how long did it go on for?

TF: I met him in 1979, but it really began in 1980. It was my sophomore year and all of my junior year. I was 17 when I got out.

How were they orchestrating this?

TF: The men behind it would call on a private line I had at my house around midnight several nights a week and demand that I appear right away. I would sneak out of my house, and they’d pick me up. They’d take me to these really nice houses all around the area. I’d go into a downstairs area where all the men were at. I remember seeing guns and money.

They would put me in a bedroom, and many men would come in and out of there over the course of several hours. Then, they’d take me home. No one ever asked me who I was, how old I was, or where I was from. Nothing like that. They went in and pretty much did their business and laughed about it. Several of the same guys that I went to high school with were in charge and always around. They were always watching me to make sure I knew who I belonged to and didn’t get out of line.

Miraculously, my dad ended up getting transferred to another state far away, so I didn’t tell anyone I was leaving. I was able to escape, and I know they were looking for me afterward and priming other people to continue this.

Flores feels prayer is just as important in combating the evils of trafficking before an outreach.

What did it ultimately culminate in?

TF: The low point was when I was taken to a dingy motel in inner-city Detroit where I was auctioned off to the highest bidder over and over and raped by multiple men. I strongly believe that, because I was left there afterward, they had no intention of taking me home. The sun was coming up, and my dad was home.

There was a waitress in the café next to the hotel I went into who helped me and called the police. They came and took me home. The policeman was nice and understood what was happening, but I wasn’t in any mental or physical position to confide in him at all. I think my parents assumed I’d been out partying. The next day my dog went missing. I received a call from these guys, heard my dog in the background, then heard a gunshot, so I wasn’t going to be talking because of the threats.

I firmly believe that they probably would’ve taken me somewhere cross-country if the police hadn’t come. When I left there that kind of affected their plans. I went back to school that next week, and they took me out during school. They’d come up to me and say, “We’re leaving now.” It still happened even after that night, but much less. I think they were grooming another girl as well. Finally, it really started to slow down at the end of the school year. They took me after school one day to someone’s house where a bunch of their friends were. It was just a bad situation. I got beat up a bit and went home. It was probably the next week or two that we got transferred.

After I moved, I’d be working as a waitress somewhere and there’d be a phone call for me, which was weird because I’d just moved there and no one knew me. Either there’d be no one on the other end or a man would say, “Hello Theresa,” and I’d hang up. Weird things would happen, but we lived a thousand miles away. I was always looking over my shoulder, and it wasn’t until my senior year in high school when I decided to call the police in Birmingham, Michigan, which is where I’d lived. I think that the police officers that recovered me may have been in Detroit. I tried to find the records of when they brought me home, but I’m not sure if they even filed any. I told whoever I was on the phone with that something had happened to me a few years ago and gave them a brief scenario of it, and they basically told me that with the statute of limitations there was nothing they could do. That was disheartening, to say the least.

What can you tell us about the men behind it?

TF: I looked into this a lot and worked with the FBI on it. It seems they were part of the Chaldean Mafia. They’re very much still involved in prostitution, weapon and drug trafficking, and are extremely dangerous. They’re primarily in the Detroit area, but have spread to the San Diego and Phoenix areas. When I was working with detectives, they told me the group was very difficult to catch and lots of people are scared of them. They’re a very rich, powerful population, especially in Detroit.

Were any of them apprehended?

TF: No, they weren’t. By the time I got the attorney general’s office to listen to me and reported the names, it was probably 12 years ago. I did an MSNBC special and was on the Today show and had to give the names of the men to be able to air the segment. They didn’t say who it was during the broadcast, but their lawyers had to do some background checks. All I know is they came back to me and said that it was good to go.

There were three main guys that went to school with me. I’m on the Facebook page for my high school graduation year, so some of them know who these guys are and have let me know that a couple have died. Those two were not the head of it though. One was shot inside a party store that he owned or his family ran. The other committed suicide. The third, who was the main guy, is still alive to my knowledge. The last time I Googled him he lived in Novi, Michigan.

This could happen in any neighborhood, though. There are many groups involved in trafficking. People shouldn’t think that they’re safe just because there aren’t any Chaldean Mafia members in their area.

Do you know how they put the word out on the street about you to others when you were being trafficked?

TF: I don’t. It’s a tight-knit culture. I was in church with a lot of them as well. I remember a high school girl I sang with in the choir — she’d made a comment about not being allowed to speak to me. I think it’s one of those things where everyone knows who needs to know. Somehow, they’re all well connected like any mafia.

Tell us how you created SOAP Project and what it does.

TF: I was giving talks and someone asked me to speak in Michigan. Obviously, I was pretty terrified to go back there, but I felt safe with this group. In the beginning, I always had police protection. One night when I went to Michigan to do a talk, I was coming home and got lost. I had a meltdown, panicked, and wondered what can I do about this? These audiences are so interested in stopping this, but I didn’t know what to tell them about how to stop it.

I have a lot of survivors reach out to me who want to help or are just not doing well. I thought, what can we do to help the girl who’s in it right here, right now? I thought of my worst moment in that hotel in Detroit and thought that’s where we need to help that girl — right there in that hotel. It just came to me. I decided what we’d do is reach out to hotels and motels where these girls are at, let them know, and educate them. That’s how it was born 10 years ago.

My team consists of survivors, counselors, law enforcement, retired firemen, and religious personnel who help in many ways, including in prayer, and are from seven states. They pay their own way to do this and work tirelessly to keep me safe, to organize the volunteers during an outreach, and to collaborate with local authorities when a victim is recognized. They also work with survivors who need advice.

Your organization distributes soap bars to these hotels in areas where you expect a high concentration of trafficking with a number to call, right?

Theresa Flores: Yes, the number goes to Polaris Project, which is in Washington D.C. It’s a 24-hour hotline. They’re one of the lead human trafficking organizations in the country. They get massive funding from the government and are a non-governmental organization (NGO).

How do you work with survivors?

TF: We don’t actually do the rescues. It has happened by chance, but we give out missing children posters along with other items. We’ve been in hotels talking to staff where these girls are standing right there, but we let law enforcement handle all that. As I was speaking, people were coming up to me saying it’d happened to them too. I could see how broken they still were. Even though I’ve been in abusive relationships, I’ve had a blessed life, went to school, and decided I wanted to help these ladies because many don’t have families and the resources that I’ve had. I started doing retreats with them. We fundraise with volunteers and pay for their airline tickets. We had 25 survivors come to our first retreat in Columbus, Ohio. We just kind of poured into them — mind, body, and soul.

We teach them classes about how to share their story in public, how to do an interview, we hold self-defense classes, teach them how to cook, and be a good mom. We have healthy relationship classes. A lot of times they’ll go into domestic violence relationships because they don’t know any better. They don’t know how to be loved after something like that. I started doing the retreats probably eight years ago and that has just blown up. We’ve had over 200 women at our retreats.

I have an office in Monroe, Michigan, where we have case management. If law enforcement recovers someone, they can call us and we’ll have someone that’ll go get them immediately. We have housing arranged with the Salvation Army to get them a bed, and the next day we can help them get their life back together. We have free trauma-trained counseling with a lady named Lennie Alcorn who is very experienced in these matters, and we have a support group that meets once a month as well. We’ve created an amazing support system that they never had before.

What do you think the most common misconception is about human trafficking?

Theresa Flores: There’s two. One is that she wants to do it. They see a woman on the street or a woman checking into a hotel that’s not dressed very nice, and they judge her without knowing there’s absolutely no way that someone would want to sell their body 20 times a night. She’s being put up to it. The other is that it only happens in other countries — people still think that.

In your TED Talk segment you referred to human trafficking as a “silent epidemic.” Why?

Theresa Flores: We have hundreds of thousands of kids being trafficked. There are 1.3-million kids missing at any given time in the United States. That’s a huge number. We should be able to get funding for everything we do, but we don’t. We have 3,500 kids a month who go missing just here in Columbus. Granted, the majority are usually recovered within the first few days following their disappearance, but those that aren’t have a much higher chance of becoming victims of trafficking. It’s an epidemic solely because of the kids, but the kids are 50 percent. There’s another whole side to it that involves adult men and women. We focus a lot on the kids because 77 percent of all kids being trafficked will go on to become adult prostitutes. They’re still considered trafficked because usually they’ll have a pimp or someone blackmailing them.

How have you taught your own children about your experiences and the world of human trafficking?

Theresa Flores: You walk into my house and see boxes of my books and flyers, so there’s no way they couldn’t know. I’ve had them volunteer for me as well. My son’s in college now and helps map out hotels for me and call them to find out how many rooms they have. My oldest daughter works part time for me, runs the whole SOAP Project, and handles all the soap orders. My middle daughter is going to be a child psychologist and graduates this year. My husband is VP of our board. Everyone in my family has been affected by my coming out and sharing what happened. They’ve all been devastated. I can remember each and every time they found out and the response that they had, from my uncle to my mom to my dad. That was the hardest time right there, so they’re all a huge part of this.

I remember one time thinking this would never happen to my kids since they know so much about it, but then I thought it was foolish to think that because I was a single mom for 10 years. If someone came up to my son, who is the only boy in the family, and said, “Hey, I got your mom, you need to go do this,” or “I know where your sisters are and you need to do this,” he’d have done it in a heartbeat. The most important thing is for parents not to be foolish. This can happen to any kid.

Something that really stood out was how your victimizers had enough confidence to do what they did and know that you wouldn’t go to the authorities.

Theresa Flores: It’s funny you say that. The two things that people probably say to me the most is number one, “Why didn’t you just tell your parents or the officers that day?” The other is, “Why did you fall for this? They probably weren’t going to do anything. Why didn’t you just walk away?” People honestly don’t even consider you’re a child. It’d even be hard for an adult. If someone came up to you and said, “I’ve got your wife, I’m gonna kill her. What’s your bank card number?” A lot of people would do whatever it took, right?

Partnerships with local groups are essential to rescuing victims around the country.

What do you think potential victims should do to stack the odds in their favor to convict the individuals behind this? The obvious answer is go to the police, but what other steps should they take?

TF: That’s tough because most victims are never going to prosecute or consider going after these guys. There are several reasons why, but that’s why we have so few convictions. We have no one to testify, no witnesses, so it’s difficult to make a case without her there. I believe that’s why they’re not getting harsher sentences. That girl just wants her life back because she’s terrified. I’m still terrified, and I’m 54 years old. I have nightmares where I’m in a hotel, there’s a knock, and they’re there. If I got a phone call from the police telling me they had one of them and wanted me to testify, I’d have to think long and hard on that. Because of that, it’s difficult to say what she could do to protect herself.

What do you think the most discouraging part of this battle is?

Theresa Flores: All of it, but the most discouraging thing is that a lot of law enforcement and higher officials are involved in this. That’s why we’re not getting anywhere. No one is going after the demand. I can give out 2-million bars of soap, and it’s not going to change it. We have to go after the guys who are buying her. This issue isn’t getting solved partially because law enforcement is sometimes involved and prosecution becomes more challenging. I hate to say it, but it’s the truth. Probably 95 percent of the survivors I know were forced to have sex with law enforcement. I wasn’t; that’s not my story, but I know quite a few.

How are victims typically targeted?

TF: A lot of it is through the “Romeo pimp.” The pimp is a trafficker and is the one going up to vulnerable girls. It could be girls who are poor, or her parents both work, or she’s just average looking and insecure — those are the ones especially at risk of this happening. Pimps will go up and befriend them or buy them nice things. One of the ways it happens is through these guys who act like their boyfriend. It’s very rarely kidnapping people off the street. I’d say the second biggest way is parents. We have a lot of family members who sell their kids, and it goes undetected. I think about 40 percent of the women who come to our retreats were trafficked by family members first.

What can you tell us about how victims are randomly prospected?

TF: Guys will look at a kid’s social media to see how many friends they have, what they’re complaining about, how often they’re online. We do hear a lot about social media infiltration and coercion. We had a 12-year-old girl in a little town here in Ohio talking to who she thought was a 14-year-old boy, and he convinced her to meet him at the library. Thankfully, she went with another friend and found out it was a 22-year-old guy, and then she alerted who she needed to and got lucky after that, but social media is a huge way that this happens.

Even interactive games like Fortnite, where you can talk to others you don’t know, those are ways child stalkers are going after them. I think they throw out a huge net to see what they can get. The kids who are smart, have good social skills, and a good support network usually escape their grasp, but the ones that don’t are the ones who get caught. A trafficker can go up to a hundred girls in one day at a mall and maybe only one will fall for their scam that starts with something like telling her how pretty she looks, but that’s all it takes.

Is there an average age for victims?

Theresa Flores: The average age of entry into trafficking is 13. A lot of the women I see, if they were trafficked by a Romeo pimp, it’s usually around 15 to 17. But then again, I think the reason the average age goes down is because you have a lot of parents, grandparents, and step-parents trafficking their kids as young as 4 to 6 years old. I have hundreds of women’s applications and so many were trafficked very young, and those are the ones that have the hardest time recovering. Those are the ones in desperate need of help.

How can parents mitigate the risk factors?

Theresa Flores: I think a lot of parents have no clue it’s going on. It’s only by educating themselves about it. Unfortunately, not many schools even talk about this. Every college freshman orientation should have a mandatory class on it, if not sooner. Parents might assume their kids know about trafficking or that they don’t let their kids go someplace like the mall by themselves, but it’s not just that. That helps, but the parents have to get good at seeing the signs of them changing. It’s really up to all of us as a community. We’ve all seen that girl when we left the theater late at night and she’s just standing there by herself. How many of us actually go up to her and ask if we can help her or if there’s anything she needs? We don’t do that, or instead, we judge her. It’s really going to take all of us as a society to change this.

Meet Theresa Flores:

Family: Married with three children

Home: Columbus, Ohio

Recommended reading list:

The Slave Across the Street

by Theresa Flores

Slavery in the Land of the Free: A Student’s Guide to Modern Day Slavery

by Theresa Flores and PeggySue Wells

Renting Lacy: A Story of America’s Prostituted Children

by Linda Smith

A Seat at the Table: The Courage to Care About Trafficking

by Celia Williamson

Theresa Flores’ Everyday Carry

Smith & Wesson .38

Damsel in Defense purse

Favorite song: “Black Water” by the Doobie Brothers

Favorite quotes: 1) “Justice will prevail.” 2) “What one generation accepts, the next embraces.”

Personal idol: Mother Teresa

Favorite place to vacation: Vegas or the beach

Coke or Pepsi? Diet Pepsi

iPhone or Android? iPhone

Favorite Holiday: Halloween

URL: www.soapproject.org

The War on Human Trafficking is not over, read more:

- Learn about the strategies of predators here.

- Here's first-hand accounts of how to fight back.