In This Article

“I don’t want to be qualified. I don’t want my accomplishments qualified,” explains a currently multitasking Lisa Jaster, graciously chatting from the car in between her children’s rugby and jiujitsu practices. “I went to the State of the Union address in 2016, and I posted a few things online. I was sick of people telling me, ‘You’re strong for a woman,’ or, ‘Wow, you’re fill-in-the-blank for your age,’ or, ‘You really know your tactics for a female soldier.’ Not only had Lisa’s gender and age suddenly become a focus, but so had her resolve. From those comments came #DeleteTheAdjective and a bit of a chip on her shoulder. “Those chips on our shoulders are what make us succeed in the long run,” Lisa explains.

She’s not wrong. Her drive has led Lisa to delete the “female” adjective in a life and career full of accomplishments. First deployment? Afghanistan after Sept. 11. Second Deployment? Operation Iraqi Freedom. Graduating from the prestigious Army Ranger School? Check. It’s an impressive feat to graduate from Ranger School at all, let alone conquer it at the tender age of 37. “In my Ranger school class, I always volunteered to be point man, or carry extra items. I remember one mission where I was a 240 gunner, which is a roughly 30-pound rig, and I had probably 100 rounds on me. As we’d conquer this mountain trail, our Platoon Sergeant would do a head count at the top. It was just one of those days, and I looked at this young guy and he was counting heads, and I elbowed him in the ribs and I laughed really hard. Later that night in the patrol base he pulls me over to the side and he’s like, ‘Why are you laughing?’ And I said, ‘You don’t get it, I get to be here.’”

Photos by John Jackson

Lisa’s zest for experience has served her well, alongside those chips on her shoulder. Currently, she wears a variety of hats — Army vet, Army Reservist, Marine wife, devout mother, Brazilian jiujitsu trainee and coach, bow hunter, and so forth. There’s never a dull moment, and that’s just the way she likes it. Ever inspirational and moving forward, Lisa took the time in her busy schedule to enlighten us on her career and resolve, and also the virtue of “going all-in” to realize your dreams. “You have two duffel bags, and you shave your head. I mean, you don’t even bring hair to school. If that’s not all-in, I don’t know what is.”

West Point graduation, May 27, 2000, shaking the hands of her company Tactical Officer and NCO.

RECOIL OFFGRID: Do you have a history of military service in your family?

Lisa Jaster: My grandfather was an Army Air Corps navigation instructor during World War II. Due to injury, he never actually ended up going over, but then he became an instructor at the navigation school. My father is a 1968 graduate of West Point and did three tours of Vietnam, received the Silver Star, and four Purple Hearts.

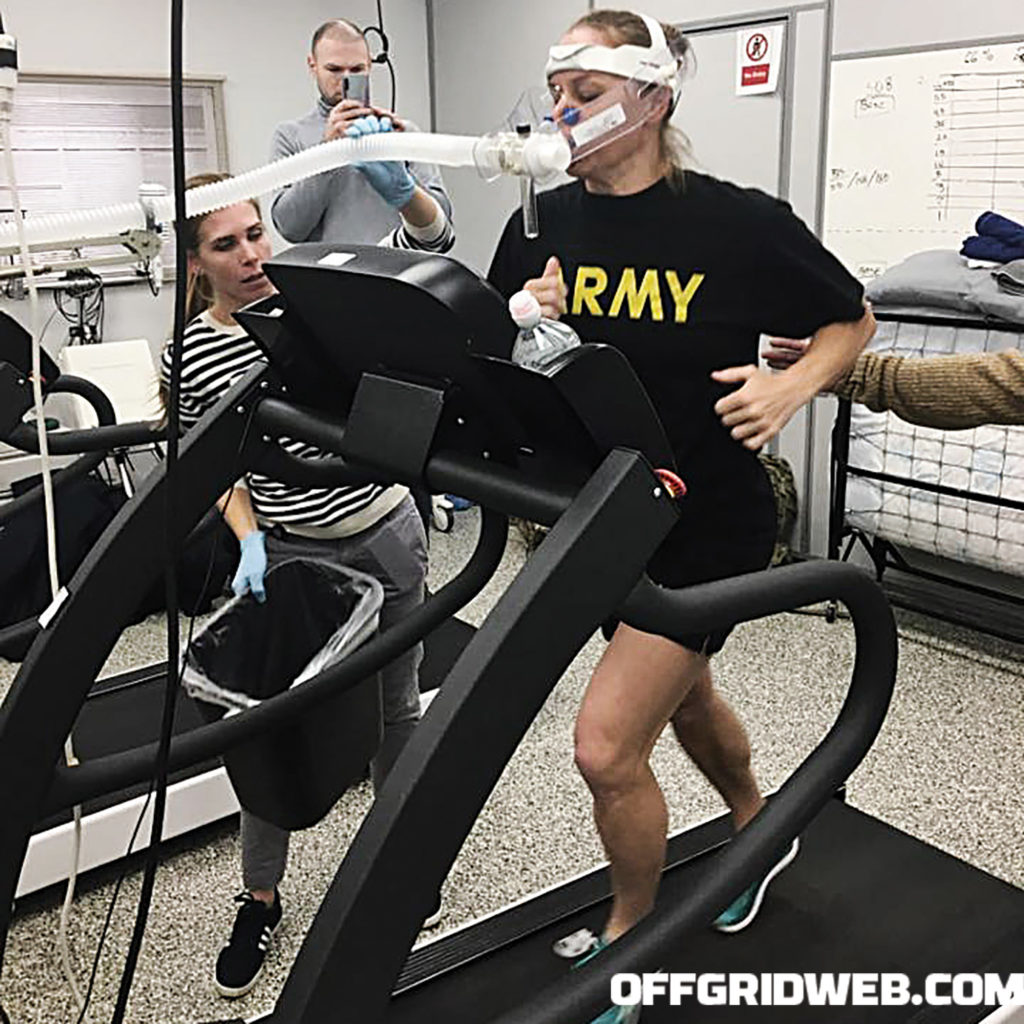

CPET testing for the “Hyperfit Female Study” at the U.S. Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine on December 13, 2019.

What were your motivations to join the Army, and more specifically to undertake the challenge of attending Ranger school?

Lisa Jaster: I actually read a book my grandmother had found and given me called In the Men’s House by Carol Barkalow, and she’s one of the first female graduates from West Point, class of 1980. As a seventh grader, it was like, “Wow, this is neat, this is something a lot of women haven’t done before. This sounds really hard.” I was living in a small town where everybody knew everybody; it was hard to really make a splash unless you were getting in a lot of trouble or you were the quarterback of the football team. So, I read this book and I thought, My God, I want to try that. And my father was a West Point grad, so he had grown up watching The Men of West Point, which was an old TV show.

New Cadet Peplinski at Camp Buckner during the field problem at the finale of “Beast Barracks” in August 1996.

How did you push forward to get accepted and make it in?

Lisa Jaster: We didn’t have the internet back in 1990-’91, so I didn’t know how to get into West Point, but I heard that you needed a Congressional nomination. I just started sending my school pictures to my congressman and my senators. Every year, I would get my school picture and I would write them a letter, and I would send it in. If there were ever any town halls where politicians came to Plymouth, Wisconsin, or anywhere in Sheboygan County, which is where I grew up, I would be sitting there with all the retirees that went to town halls. Finally, between my junior and my senior year of high school, I got to go to a West Point summer camp. And they marched us, and they had real cadets teaching our little classes, and we did intramurals and got to wear the cadet intramural jerseys, and sleep in barracks, and I just thought it was the neatest thing ever. And I thought, Well, if I don’t go this school, I don’t want to go anywhere. And that was it. It was definitely a good fit.

Ranger (Major) Jaster on the lowers rappel wall at Ranger School.

Can you break down your career in the service?

Lisa Jaster: I went to cadet basic training in 1996 and was commissioned in 2000. September 11 happened, and right away at the start of 2002, we went to Afghanistan. After returning from Afghanistan, we went to Iraq for Operation Iraqi Freedom I. I came back, went to grad school, and then went to South Korea for two years, and after that I got out of the Army. I got recruited for a unit after being gone from the military for about three years. Turns out I had been completely processed out, but didn’t know it, so it took me two years to get back in the Army as an Army Reservist, which is my current designation. I had to go through everything, although not basic training, but I had to prove that I really wasn’t as old and decrepit as I felt.

As you were entering, what kind of physical prep did it take to get you to where you at least physically felt like you were ready to go to West Point?

Lisa Jaster: Well, teaching myself to run at least two miles was a challenge. I danced ballet, tap, and jazz, and played soccer in high school. I was also cheer captain, but that didn’t really prepare me a whole lot for the Army fitness test. In high school, maybe junior year, I started trying to run on a regular basis, doing a mile a day, three to four days a week. By my senior year, I was trying to bike everywhere, and when I wasn’t biking I was running or walking. I tried to incorporate physical activity into every aspect of my life, and then I actually took a weight-lifting class in high school, and got taught how to lift, which it turns out is another addiction that I’ve held onto ever since then. I would say between dancing as a kid, having older brothers and stepbrothers as a kid, and then as an adult doing martial arts, specifically Brazilian jiujitsu, that’s enough to get anybody prepared for most situations.

Above: Major Lisa Jaster at the State of the Union in 2016 with most of the Chiefs of Staff. From left to right: General Neller, General Milley, Jaster, General Dunford, Admiral Zukunft, and General Grass, January 12, 2016.

What about the mental stuff? How did you overcome the mental challenges of becoming a Ranger?

Lisa Jaster: I think the mental portion wasn’t as hard for me because I already had a lot of life experiences. I’d been to Afghanistan and Iraq in the beginning, when we didn’t have showers and when we weren’t sure if we were going to get real food resupplies, and when we’d eat MREs for a week before we’d get some more T-rations, before there was MWR and everybody was stealing smokes and shoes. I’ve pulled all-nighters with colicky babies, and I’ve been the wife of somebody who was deployed to a combat zone as a reconnaissance Marine, so I’d already been through all those things. I literally had duffle bags older than some of my classmates. The hardest part about it was that I missed a lot of birthdays and a lot of firsts for my kids because my daughter was really young at the time.

What types of support or criticisms did you get from your colleagues?

Lisa Jaster: By the end, I was the lone female. It was really exciting for me to see how all these young male officers and enlistees were growing and developing, but also how they looked at me differently. Day One, I got “the looks,” but by Day Five, it’s, “Hey Jaster, can you just grab this for me for a minute? Hey Jaster, can you help me out?” And to see how their perception changed from “women shouldn’t be here,” to just becoming part of the team.

Major Lisa Jaster with the 32nd Under Secretary of the Army, Patrick J. Murphy, January 12, 2016.

How else did gender impact your experience?

Lisa Jaster: From day one I got glared at. I mean, having women at the school was changing everything. None of these young, high-speed alpha males wanted to be graduating with the first women. There are a couple reasons: the mindset that “obviously the class must be easier if women can graduate;” and fact that the media showed up for everything. Women being there took away from the accomplishment of our classmates as well. We got all the attention. My graduation day was just as important for the other 88 graduates who stood out there as it was for me, but there were 100 cameras facing me. If I could go back and change anything, that would be one thing I would change. I would figure out a way to reduce the hype about me and focus on everyone’s accomplishment. There were, of course, some guys who came in and were like, “This is awesome, I have a daughter, I can’t believe you’re here, I’m behind you.” But even they had to deal with the fact that there were so many eyes on us that things were going to be scrutinized.

How were you able to gain respect and blend in?

Lisa Jaster: For my class, just under 400 people showed up for Day Zero. Less than 75 percent of us made it to breakfast on Day One, and Day Zero’s just filling out paperwork. RAP (Ranger Assessment Phase) week is full of individual tasks, all the testing, you run everywhere, you’re doing push-ups every five minutes. I mean, you eat and you run, and then you have to do a bunch of push-ups. I will not lie, I may or may not have thrown up a few times. You’re pushing yourself to your max, and at some point in time you look at the person next to you and you say, “I don’t care what you look like, I don’t care what you sound like, but you better hold your own because every time you drop your bag, or every time you don’t do a push-up, all of us get punished.” So, for the students, that gender animosity lasted four days or less, tops. There were eight women who made it through RAP week, so as soon as the “Crazy Eight” got really integrated with their squads and were holding their own, our classmates were like, “OK, physically these girls have it.”

Eventually as classmates, we were able to bond and meld, but the Ranger instructors had to go home to all the media. I had no idea what the public was saying about the Ranger women, but I know those Ranger instructors went home and would get text messages from their buddies, or people who were uninvolved, but had such a strong opinion about gender integration. They had to come back the next morning and be professionals. They had to force themselves to ignore everything. So even though, yes, we did get treated differently, the professionalism of the instructors was phenomenal, because I can’t fathom that amount of pressure.

From your perspective, what are your thoughts on the roles of women in combat and the military in general, and what do you think can be improved?

Lisa Jaster: I don’t have a lot of complaints. I’m 42. So, at 42 my worldview is very different, but I’ve been really blessed that I went to West Point, where as soon as someone wanted to give me a hard time, I could compete against them, because I trained. As far as what needs to change, I think a lot of times it’s just perception. And if you can get acquainted with a Lisa Jaster, or Shaye Haver, or Kristen Griest, or any of these people who break the mold, the perception of what society dictates doesn’t necessarily fit.

Above: Handstand near the top of North Franklin Mountain, outside of Fort Bliss, Texas, with her soldiers upon return from their deployment to Iraq, October 27, 2018.

In fact, one of the things I’m most excited about is the Army has created this gender-neutral, age-neutral PT test. The requirements are different based on your job, or a job category. I never wanted lower standards because I am a woman, because I didn’t think the job required “female standards.” When I came back in the Army I was an old captain, and based on my age, I didn’t have to do as much physically, or be in as good of shape as somebody younger than me, but I was expected to do the same job. I would not be OK with a doctor who was a little “rusty” and less knowledgeable because they were older. If physical fitness is part of my job, and there’s a job requirement for a level of physical fitness, then that’s what I need to be judged by.

Above: Shooting a Lapua .338 while filming the 5.11 Ghost Recon: Breakpoint Challenge at Shoot Las Vegas, Nevada, on September 6, 2019. Photo by WodHawk Photography

In terms of combat, where have you served, and what have been some of those tougher experiences from some of that time?

Lisa Jaster: I have never referred to myself as a combat vet. I can’t imagine referring to myself that way. I do have a combat action badge, but I have not seen anything that’s book worthy, shall we say. There’s a part of me that wishes I had been challenged more than I was, but there’s another part of me that knows that what I bring to the battlefield, or what I bring to the fight, was at a strategic level and not at that individual tactical level. I was an engineer who did minefield clearing operations, area clearance activities. There were a lot of people who were safer because of the activity I did, and what I was doing. I’ve got a master’s in civil engineering, and I was able to use that in all three of my deployments.

“Glamour Shot” taken while filming the 5.11 Ghost Recon: Breakpoint Challenge somewhere in the desert outside of Las Vegas, Nevada, on September 7, 2019. Photo by WodHawk Photography

How long did you serve total, and what was your highest rank that you reached?

Lisa Jaster: I did seven years of active service, and I am at seven and a half, almost eight years, of Reserve service. This last summer I was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel, and in May I will be taking Battalion Command.

Above: A typical day at the ranch during hunting season with the family, fall 2016.

Do you have any other regrets on your service, or anything you wish you had done differently?

Lisa Jaster: I always wanted to go to Sapper school, and never really had the opportunity, so that’s one of those things I wish I could have done. But that’s not a regret, that’s just something I didn’t have the opportunity to do. I made some big mistakes. I’ve said some things. Sometimes there’s things that I’m still mulling over to this day, but I must honestly say that I’ve been glad for every single mistake in the long run. My husband has a great quote, “It’s not about the stressful situation, it’s how you react to it.” And I really look now to see how people react to those situations, rather than what bad situations they’ve put themselves into.

Are there any achievements or milestones that you’re most proud of?

Lisa Jaster: I’ve got a funny story — I don’t know if it’s a proud story. I have gone through my military career, and one of the first things was September 11. I was QRF (Quick Reaction Force) commander at Fort Stewart working directly with the MPs. My engineering unit had three teams that rotated through on a 15-minute, four-hour and eight-hour recall for the base, and I got to lead one of those teams. And then the next thing I did was go to Afghanistan for Operation Enduring Freedom I, and my very first achievement medal was a Bronze Star. So, I am a young lieutenant with a very naked uniform and a Bronze Star, and when I was a major I told my battalion commander that. He saw my DA photo and said, “You don’t even have an Army Achievement Medal (AAM).” And I laughed and said, “All I have are deployments and company command time.” All my Lieutenant time was either in Afghanistan or Iraq, and then my Captain time was in Korea. So, it’s all been big events, and he just laughed at me and I said, “But whatever you do, I don’t want any more awards because getting those award racks built is really expensive.” I ended up beating him on the next Army Physical Fitness Test, and in formation, he gave me an AAM, which is the lowest achievement ribbon. I had to get new award rack, new pictures, new everything, and it was kind of this funny, “How dare you give me this award.” Still, it’s an AAM; it’s an award, and it means something to me.

So fast-forward to now, these days. What are you focused on?

Lisa Jaster: We recently moved so I could start a new job with a new company, but I have a lot more control of my situation, and a lot more impact. The negative is that it’s hard for me to just break away and go train jiujitsu five days a week like I did before we moved. I do CrossFit-style training four to six days a week, Brazilian jiujitsu three days a week, and I also I try to help where my kids train jiujitsu, and maybe help teach a kids’ class once a week. For military skills, it’s important for me to keep up with ruck running, vest runs, normal PT stuff, as well as shooting handguns and long-guns. Myself and my husband are both concealed-carriers, so I do try to still get to the range regularly, but not as much as I would like. I like bow hunting as well, and my next goal is to kill a turkey with my bow.

What would you still like to conquer at this point in your life?

Lisa Jaster: I would love to compete in Brazilian jiujitsu. Part of the difficulty of that is the amount of 42-year-old, 140-pound women who want to compete in Brazilian jiujitsu is pretty small, so it’s hard to find people to get matched up with in tournaments. A lot of times I show up and there’s nobody in my bracket, and it’s either I fight the 22-year-olds, or I fight the 160 pounders. Of course, I’m more than willing to do both when I have the opportunity. It’s a discipline where being smart matters; it isn’t just youth, it’s also skill and endurance.

Jaster family at the Houston National Cemetery, Memorial Day 2017, placing flags near the graves of veterans with other members of Team Red, White, and Blue.

What do you think about the plight of veterans suffering from PTSD?

Lisa Jaster: I would like to see our medical system get a little less fearful of natural solutions. Most of the prescription drugs have severe side effects and limit a person’s capabilities, such as operating heavy equipment — for my engineer soldiers, that takes away many of the jobs they are best suited for. Engineers are definitely not the only ones. We’ve lost quite a few of the guys I deployed with in early 2002-’03 due to unseen injuries. Well, what can you expect if the medical solution to PTSD removes so many civilian work opportunities? These are not the type of people who want to collect a welfare check and pity from others. So, many self-medicate, abuse alcohol, or try to “suck it up.” If there are non-addictive, natural alternatives to antidepressants which can help veterans and others suffering, then there is a chance that PTSD could end up with a decreased mortality rate.

You’ve certainly had an interesting life. What’s the best part about being such a diversely accomplished woman?

Lisa Jaster: Being in the military has exposed me to so much more of the world than I ever knew existed. Getting a behind-the-scenes view into the psyche of so many hard-charging soldiers, such as at Ranger School, showed me that these guys still love their kids, want to be impressive to their loved ones, and need a support system like everyone else. Being a soldier, wife, mom, and manager allows me to see the vast complications of every situation and gives me empathy. I am blessed to live outside my comfort zone and constantly surprise people who think they know me because of an adjective.

Lisa Jaster’s EDC

Pistol: SIG Sauer P365

Holster: Custom Blacksmith Tactical IWB Flex Rig

Knife: Gerber Paraframe

TQ: Army issue tourniquet in a Fieldcraft Survival tourniquet holster

IFAK: Adventure Medical Kit Trauma Pak

Flashlight: SureFire E2E Executive Elite

Lisa Jaster

Hometown: Plymouth, WI, and now New Braunfels, TX

Age: 42

Education: MS in civil engineering from Missouri University of Science and Technology; BS in civil engineering from the United States Military Academy at West Point

Family status: Married to a Marine Reserve Colonel with two kids (son, 11; daughter, 8)

Military accolades: Airborne, Air Assault, Ranger, a few deployments, and a couple of ribbons

Favorite movie: Tie between Hitch and Pitch Black

De Niro or Pacino? Gotta go with De Niro

Top 5 recommended books:

Ashley’s War by Gayle Tzemach Lemmon

Good to Great by Jim Collins

Outliers by Malcolm Gladwell

The Mission, The Men, and Me by Pete Blaber

Atlas Shrugged by Ayn Rand

Childhood idol: Linda Hamilton circa Terminator 2. She was a badass and when I read how she prepped for the movie, I wanted to be that focused on my goals.

Daily motivation: The fear of only being able to look back at who I once was versus striving toward who I could be

Favorite band: Metallica “Fade to Black” and earlier

Website: Facebook (Lisa Jaster – Delete the Adjective) and Instagram (@lisaajaster)

Morgan “Rogue”

Morgan “Rogue” Lt. John Nores

Lt. John Nores