In This Article

When it comes to protecting against COVID-19, the gold standard of respiratory protection is a mask that’s rated at N95 or better. However, N95 masks are also in high demand and short supply right now, even among medical and law enforcement personnel working on the front lines. This means that, as mentioned in the recent DIY mask article from No One Coming, we may forced to choose “the best of bad choices.” Still, this doesn’t mean that you should just grab a worn-out shop rag and wrap it around your face. Some kinds of household mask material are clearly better than others. Strike Industries set out to demonstrate this principle in a recent informal experiment.

Before we continue, we want to make a few things clear. Strike Industries is a manufacturer of gun parts. They are not medical professionals, nor do they claim to be. None of the following should be considered conclusive research or medical advice. This informal experiment was conducted to get a rough idea of the filtration efficiency of a handful of commonly-available household items, which might be used to make masks if no other supplies or purpose-built masks are available. The company wanted to gather this information to help its staff, their loved ones, and the gun community as a whole so we can all make better-informed choices in the event that we’re forced to make DIY masks at home.

The Mask Material Experiment

An N95 rating means that a mask is capable of blocking at least 95% of 0.3 micron particles during official test procedures. So, the obvious goal for any DIY mask material is to get as close as possible to this level of filtration, even if it can only be measured using a less-rigorous procedure. Strike Industries purchased a CEM DT-9881 Air Particle Counter to measure each type of DIY COVID-19 mask material at a duration of 60 seconds (2.83L of flow). The resulting filter efficiency was recorded for 0.3 micron and 0.5 micron particle sizes.

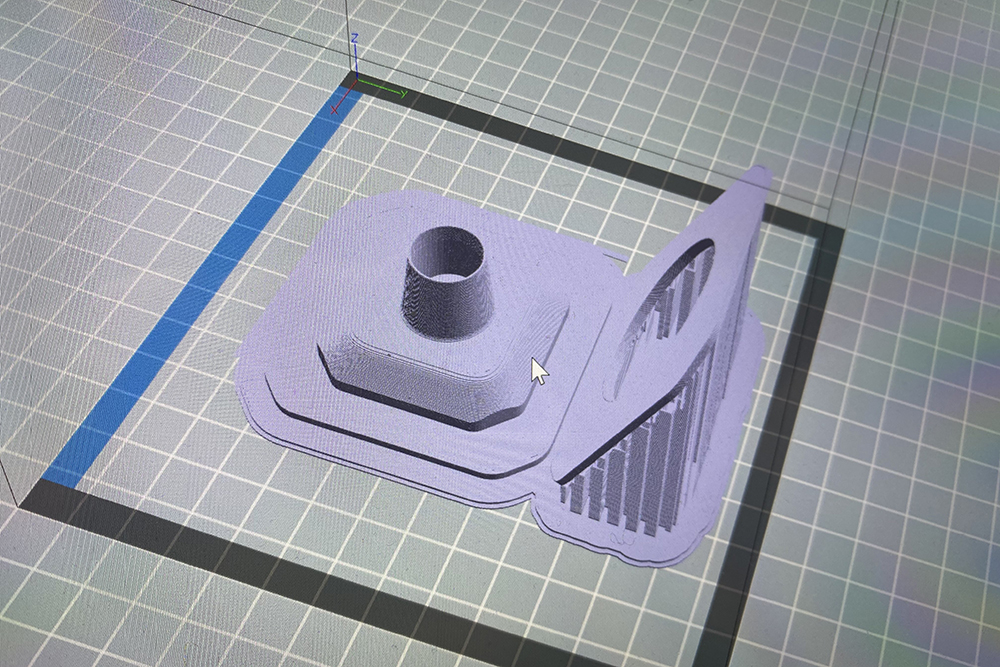

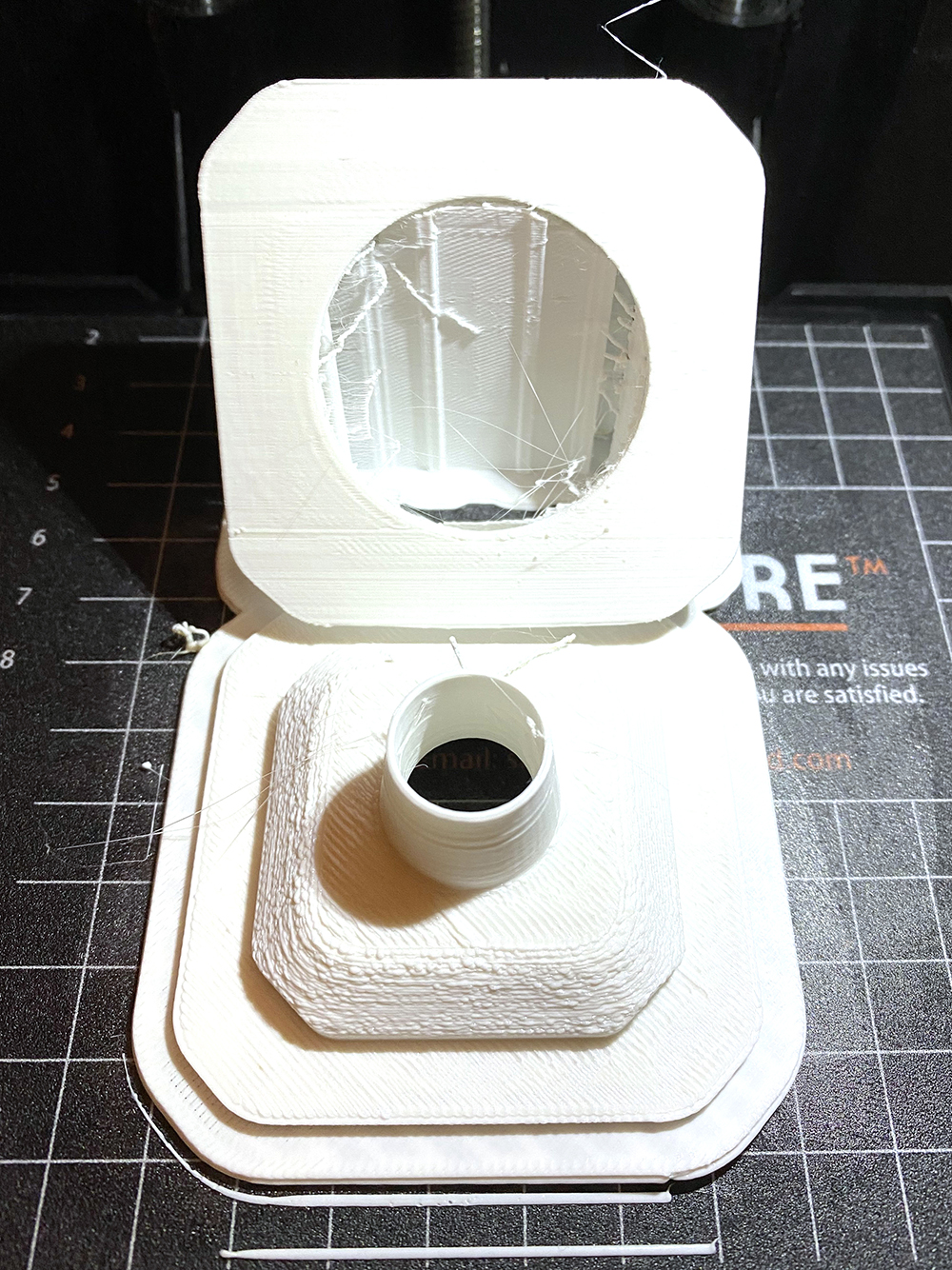

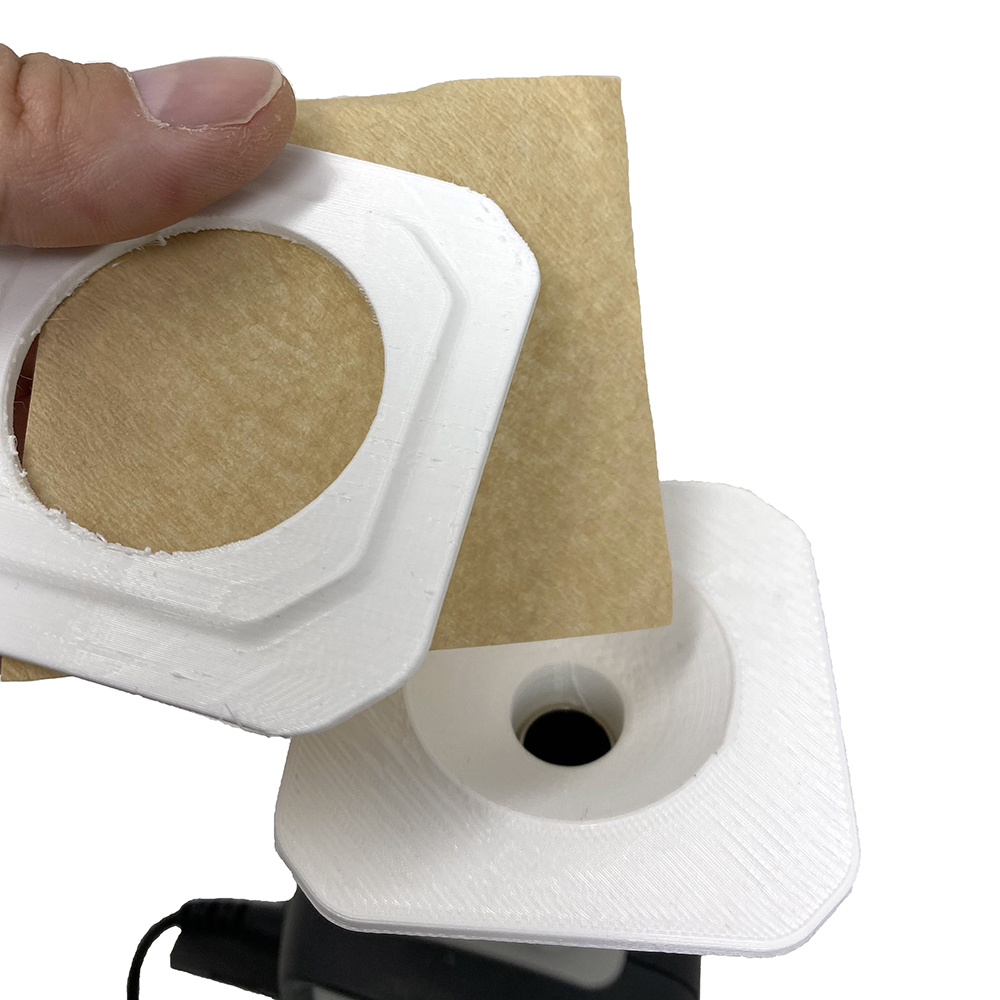

In order to consistently attach mask material to the particle counter, the company modeled a custom material holder in CAD software, and used a 3D printer to produce the holder.

Samples were placed into the holder, and held in place using four metal binder clips, as shown below.

Tested DIY Mask Materials

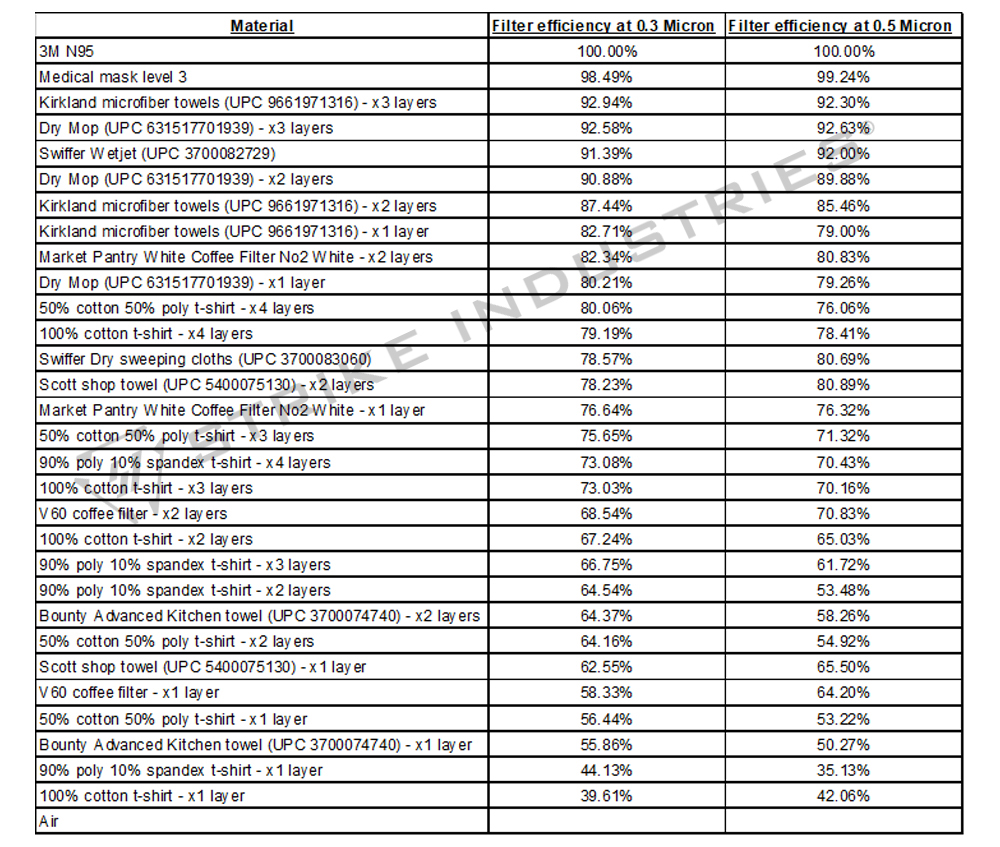

Thirty different mask material combinations were evaluated, ranging from an ordinary cotton T-shirt to a 3M N95 mask. Many of these materials were tested in various levels of layering, since scientific research has shown that multiple layers of filter media can produce better results.

Here’s a complete list of the mask materials that were tested:

- Open air (control)

- 3M N95

- Medical mask level 3

- V60 coffee filter – 1 or 2 layers

- Swiffer Wetjet UPC 3700082729

- Swiffer Dry sweeping cloths UPC 3700083060

- Scott Shop towel UPC 5400075130 – 1 or 2 layers

- 50% cotton 50% poly T-shirt – 1, 2, 3, or 4 layers

- 100% cotton T-shirt – 1, 2, 3, or 4 layers

- Bounty Advanced Kitchen towel UPC 3700074740 – 1 or 2 layers

- 90% poly 10% Spandex T-shirt – 1, 2, 3, or 4 layers

- Market Pantry White Coffee Filter No2 White – 1 or 2 layers

- Dry Mop UPC 631517701939 – 1, 2, or 3 layers

- Kirkland microfiber towels UPC 9661971316 – 1, 2, or 3 layers

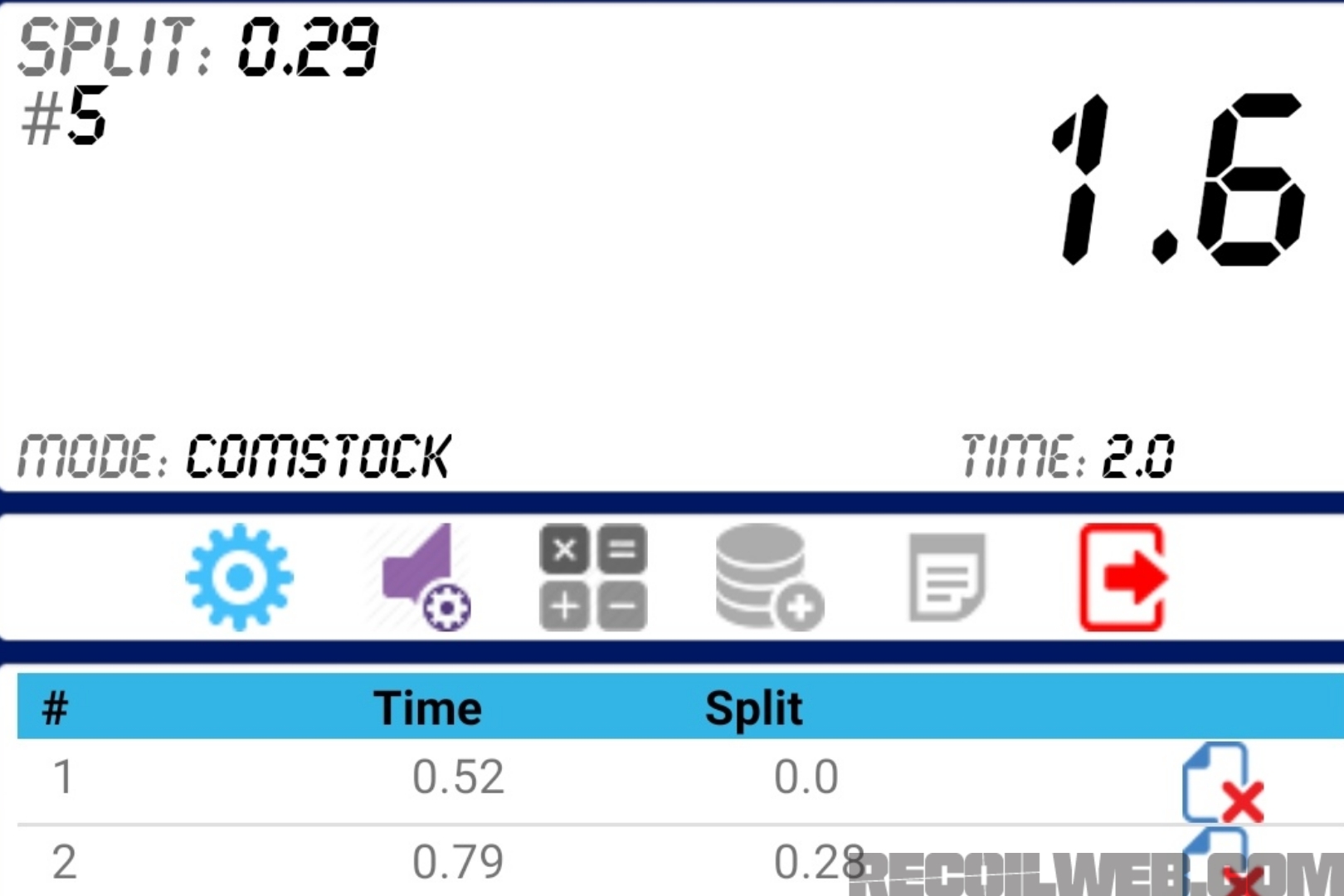

Here are the results of Strike Industries’ experiment:

Unsurprisingly, the 3M N95 topped the chart with a 100% result, and was followed closely by the commercial medical mask at 98.49%.

The next runner up was a triple-layered stack of Kirkland microfiber towels, which produced a 92.94% result. However, the test log noted that breathing resistance is high, which might lead to leaks around the edges of the mask if it’s not properly sealed against the wearer’s face.

The second place for DIY mask materials was a triple-layered dry mop pad, which trapped 92.58% of particles during the experiment. The test log theorized that the static electricity effect of the dry mop pad maintained high efficiency despite this material’s low breathing resistance.

In third place was the Swiffer Wetjet at 91.39%, which features multiple layers of non-woven fabric and a strong static electricity effect. It is noted that breathing resistance was low.

Other Mask Considerations

Obviously, there are many other factors at play beyond the effectiveness of a DIY mask material. If the mask fits poorly, absorbs moisture quickly, or makes it difficult for the wearer to breathe, it may end up being impractical at best. The experiment notes stated that it may be best to avoid coffee filters, blue shop towels, T-shirts, and kitchen towels as a result of their poor performance compared to other materials that were tested.

It’s also worthwhile to note that the materials mentioned in this experiment will likely work best inside a stitched mask sleeve with a filter pocket, nose piece, and secure straps. This will allow the mask to fit the contours of the face and form a better seal. Mask holders should also be disinfected regularly to eliminate any residual particles.

Strike Industries covers a few other mask facts and tips in the following video:

Closing Thoughts

When Strike Industries reached out to us with this information, they clearly stated that they are not medical professionals and that this experiment should not be considered conclusive research. However, they wrote, “We want to have as much information to protect the staff and our loved ones. We feel we covered a lot of useful information, and we wanted to share with the gun community to spread the word on what you can decide to do to for yourselves.”

In an ideal world, we’d all have a huge supply of N95 masks set aside for times like these. But during the current COVID-19 crisis, we may be forced to turn to less-ideal solutions. In that case, it’s wise to carefully consider which household materials might serve you and your family best if you need to improvise some masks.