Illustrations by Cassandra Dale

With your friendliest smile, you walked up to the stranded motorist and said, “Hello sir, can I give you a hand?” From the headlights of your own vehicle, you could see him well enough in the darkness. His expression seemed to be one of relief. He pumped your handshake hard and offered his prolific thanks for your help. Instinctively, you profiled the stranger and checked your surroundings. He wasn’t dressed like a country boy (even though you were in a rural area), and you could see numerous tattoos peeking out from his shirt collar and sleeves. A few spider webs and skulls ran across the man’s visible skin. No big deal, you reasoned to yourself. Plenty of people have tattoos these days, you thought. But little red flags kept popping up.

His urban clothing style just didn’t match with the pastoral area you were traveling through. So what if his apparel seems odd, you rationalized, maybe that’s just the new style. As you considered the whole scene again, you realized that there wasn’t a rear license plate on the car either, and the other stranded motorist accompanying this man was a rather rough-looking young woman sitting in the disabled car. Still focused on your good deed and with your spouse waiting in your car, you took a gander under the hood as the young woman got out of the distressed vehicle to “stretch her legs.”

After some amicable chitchat with the man, you decided to try jumper cables. As you turned back to your vehicle for your tool kit, the man’s demeanor changed abruptly. He blocked your path and gave you a sharp shove backward. That’s when you spotted the rough woman near the front of your car — and in the bright headlights, the flash of shiny metal called your attention to her hand. As soon as you realized that the object she held was a knife, your skin started to crawl, and you felt sick to your stomach. Before you could take another step toward the knife-wielding woman and your unsuspecting spouse, the man drew a small revolver and aimed it at your face. His thumb pulled the hammer back, and a malevolent grin spread from ear to ear. He had you and your spouse right where he wanted.

In this chapter of RECOIL OFFGRID’s “What If?” column, we see that the most ordinary situation can flip on its head and become a deadly set of circumstances. To challenge our judgment, the editors have played against our natural instinct to help other stranded motorists and taken us down a dark road where no good deed goes unpunished. We’ll look at some of situational awareness skills and safety strategies you’d need when dealing with potential predators on the roadside. And maybe we’ll all think twice about stopping to help people after dark. Con games come in all shapes and sizes, and so do the bad guys.

The Scenario

Situation Type

Roadside breakdown

Your Crew

You and your spouse

Location

Highway at night in an area only marginally familiar to you

Season

Summertime

Weather

Clear; high 90 degrees F daytime, low 72 degrees F at night

The Setup: You and your spouse spent the weekend visiting friends out of town. Your friends live several hundred miles from your home, but both of you were able to take a day off from work. So you drove two-and-a-half hours on Friday evening to crash for a few days of grilling and catching up. You spent the weekend laughing at the same jokes and telling the same stories you always do, downing cocktails and burgers. You meant to get on the road first thing Monday morning. But gossiping with old friends was too much fun, and it’s now 10 p.m. on Monday night. You and your spouse are cruising down a two-lane state road that winds through mile after mile of open country, dotted with the occasional one-horse town. You’re about halfway home, at least an hour from either your friends’ or your home. All your favorite radio stations are mostly static, and cell reception is a measly and inconsistent one bar for both of you.

The Complication: On a particularly lonely stretch of road, you see a single vehicle on the side of the highway. Its hazard lights are blinking, and the hood is up. As you get closer, you slow down, noticing a man leaning against the passenger side of the vehicle staring at his phone. Your spouse suggests that perhaps you should stop and offer assistance. You know this situation presents a potential threat. But your significant other reminds you that this is rural country and people tend to be more neighborly out here and, while your concern is legitimate, you might be overreacting in this case. Your spouse then asks what good it is to keep your trunk stocked with medical supplies, food, water, and tools if you can’t “pay it forward” and do a good turn for somebody who’s having a much worse night than you are.

Maybe your better half is right. You’ve had a great weekend. You’re relaxed. The night is cool and quiet, but summertime highs were certainly high earlier this afternoon. Who knows how long that poor guy has been stranded. Besides, it never hurts to have a few extra karma points in the bank. So you pull off the road, leaving at least a car length when you park behind the broken-down vehicle. You ask your spouse to stay in the car while you get out and approach the man. You notice a woman sitting in the passenger seat. After introducing yourself and offering help, the man pockets his phone and thanks you profusely. He guides you to the open hood and starts gesturing at the engine and talking vaguely about some mysterious noise before the car “just died.” You’ve changed flat tires and oil in your day, but you’re no mechanic.

While the two of you talk about possible causes, the woman in the passenger seat gets out and begins walking toward your vehicle. Your attention shifts to her, and to your spouse, but the man continues to harangue you. Except now he starts to ask where you’re coming from and going to, and how far from home you are. You gently guide the conversation back to the problem at hand, offering to break out the jumper cables and give that a try. When you turn to head back toward your car, the man stands directly in front of you and shoves you back a step. Over his shoulder, you see his female companion slash your front right tire. You turn your attention back to the man, who is now holding a small pistol. The woman is leaning into the window of your own car, her head and arms inside the vehicle. Somewhere in your mind it registers that both right side tires are now flat. You’re not sure exactly what’s going on, but those karma points you were hoping for seem to be on the wrong side of the board in this situation.

Combatives Expert Chad McBroom’s Approach

Preparation

Vehicle & Gear Check: Having lived in rural areas most of my adult life, I’ve grown quite accustomed to the dangers of traveling underdeveloped state highways with little infrastructure. Before leaving our friend’s house, I would make sure the car is topped off with fuel and do a pre-flight inspection to make sure the fluids are at appropriate levels, and the spare tire is inflated.

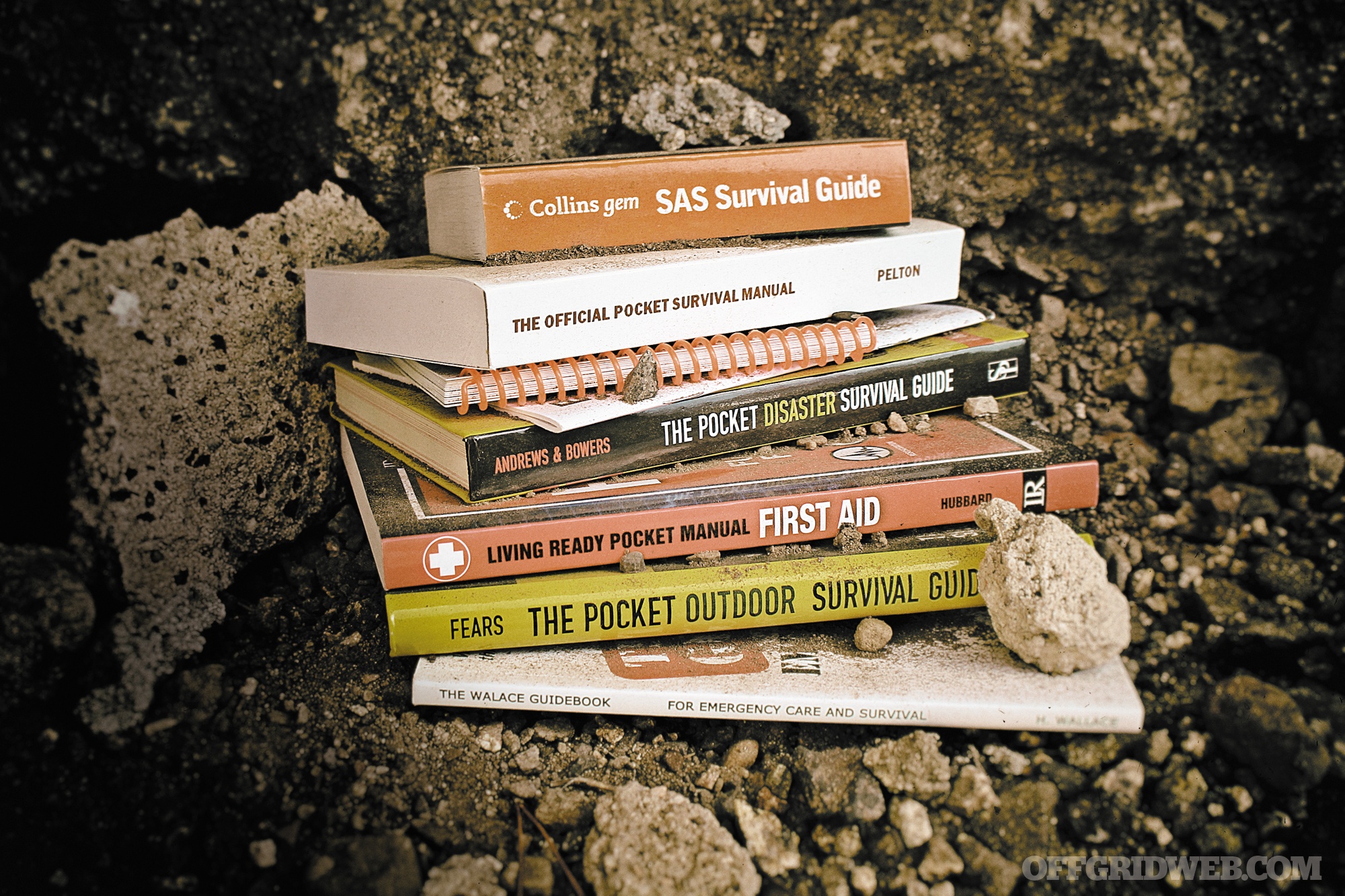

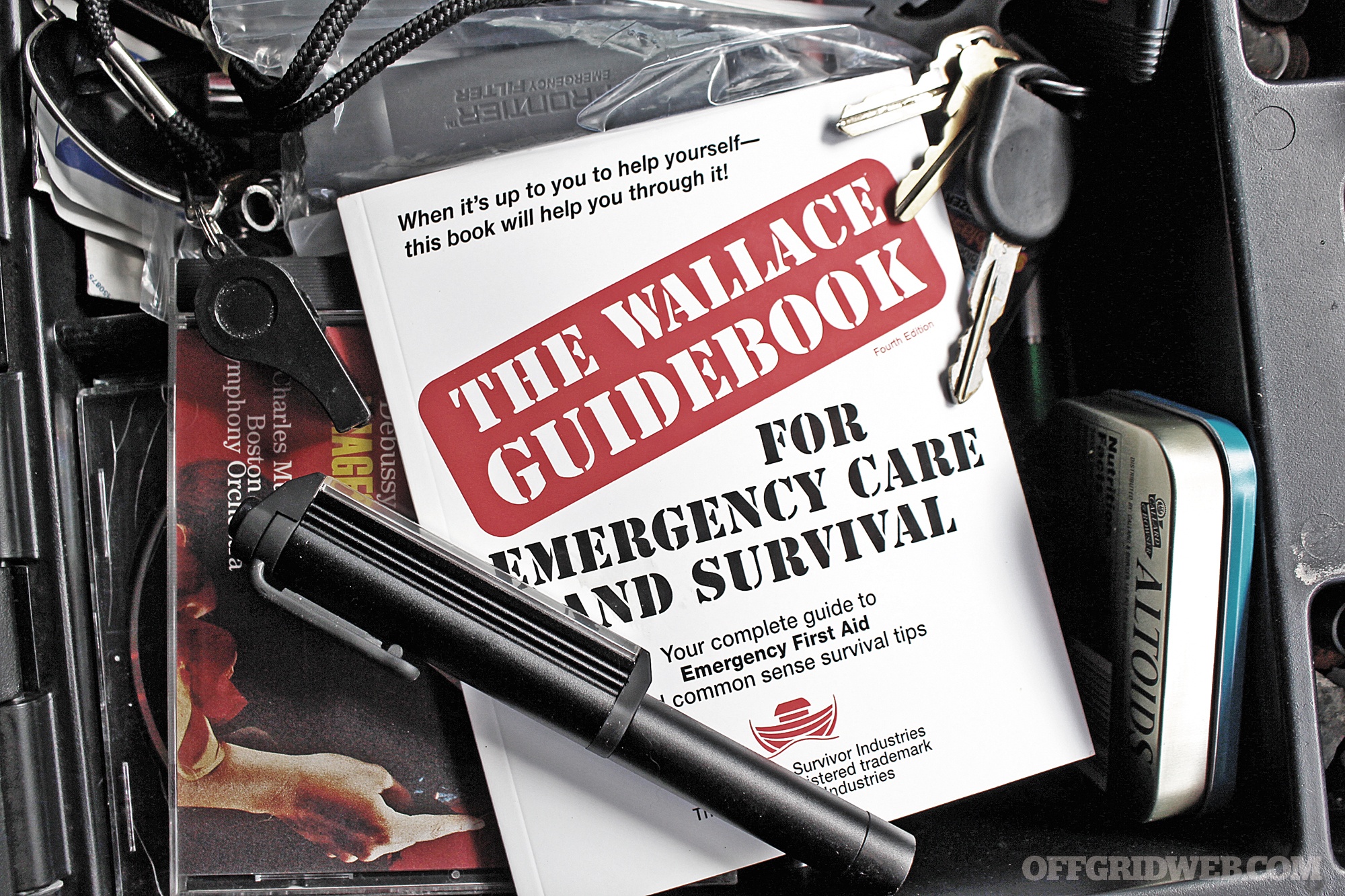

I’d also do a thorough gear check to make sure all the emergency items we brought with us are still in the vehicle. This would include a TCCC-enhanced medical kit, bottled water, lightweight cold-weather gear, emergency foil blankets, a lockout kit (i.e. lock picks, door shims, etc.), flashlight, spare gun magazines, and a portable charging pack with appropriate phone cables. I’d also do a self-pat-down to make sure I had my standard EDC equipment, including knives, firearm, wallet, cell phone, and flashlight.

Route Check: In a day and age when our cell phones are always by our sides, we tend to rely on them a little too much when it comes to communication and navigation — and not enough when it comes to investigation.

Bad cell service can ruin your day when you’re dependent on your phone to navigate an unfamiliar area. When I know I’ll be operating in an area where cellular and, more importantly, data service is spotty, I’ll download the area maps onto my phone’s navigation app. GPS coverage is usually decent even when you can’t hit a cell tower, so having the maps stored will allow me to navigate without phone service. As a backup, I always like to have a physical map of the area. Even though I’m probably familiar with the route, I want to have it in case I have to change course.

A little bit of internet investigation will tell me if there have been any recent crime patterns or notable criminal events near the area I’m traveling. I’m looking for identifiable patterns that may indicate any specific types of threats, aside from the random criminal activity. I’m also looking to identify any stretch of highway that may be more accident-prone than others so we can exercise additional caution along those sections.

Gut Check: I believe I have a certain moral obligation and civic duty to help those in distress. I also realize the unfortunate reality is that there are predators among us who will play the role of a wounded animal to lure their prey into striking distance. I try to listen to my gut when it comes to helping others in distress. Our brains can take in a lot more information than we can process. That “funny feeling” we get about a situation is usually our brain sending warning signals based on observations that we just haven’t had the time to process.

On Site

I look at every situation to consider which scenarios are the most likely and the most dangerous. In this case, the most likely scenario is a stranded motorist who has broken down on a desolate stretch of highway, has no phone service, and is in need of assistance. The most dangerous scenario is a staged breakdown to lure in a victim for an ambush. Thinking this way keeps me on my toes and helps me to remember to keep my guard up and look for anomalies that may indicate the latter.

Since we decided to stop and render aid to this couple, I want to place my own vehicle in a position that maximizes my reactionary gap, offers the best protection from other vehicles, and provides the most amount of cover for me and my wife. For this reason, I park my car two car lengths behind and offset so the left side of the stranded vehicle aligns with the center of my car. I turn the wheels to the left, facing the road, to add additional cover and ensure that my vehicle will tend to move away from the scene in the event another motorist strikes my car from the rear. This also preps my car for a fast withdrawal if necessary.

I switch my headlights to high beams to light up the area and create a wall of illumination that will conceal activity inside our vehicle. Before getting out to approach the stranded vehicle, I do another self pat-down and check my phone for service. Then, I get out and have my wife move to the driver’s seat. I want her to be able to haul ass out of there if things go sideways, a plan I quickly discuss before leaving her behind. Using my headlights to my advantage, I walk outside the cone of light to avoid backlighting myself and mask my movement.

As I approach, I’m looking for cues that might indicate whether this is a legitimate breakdown or a ruse. Does he have a flat? Is the radiator steaming? Are there any signs that this car is disabled? What about signs to the contrary? Is the car running? A running engine would not only be a contraindication, but would suggest the occupants are planning a quick getaway. How about the lights? The driver might choose to leave the lights on so they can be seen at night, but this also tells me the battery has some juice, so I might be a little suspicious if the occupants tell me their battery is dead.

I’m also looking at body language. I’ve already observed anomalies. I just checked the cell coverage and there’s no signal here, so why is this guy staring at his cell phone? Why is he standing outside, leaning against the door, while the female occupant sits inside the car? That’s two anomalies right there.

I stop about 4 feet away to maintain a reactionary gap and begin talking to the man, keeping my hands in a natural, non-threatening position at sternum height. My hands are in a position where I can defend, strike, or go to a weapon quickly and efficiently, without appearing aggressive or defensive.

I spot a third anomaly when the passenger gets out and walks toward my vehicle. Normal behavior would be for her to converse with the person rendering assistance. The presence of three anomalies tells me something is off-kilter, and I begin gearing toward the most dangerous course of action.

Crisis

The overt actions taken by the two seemingly stranded motorists confirm that we’re now in a “most dangerous” scenario. The act of placing himself between me and my wife while his partner slashes our tires indicates they’re using a divide-and-conquer strategy. It also tells me they’ve planned and rehearsed their assault, because he knows exactly what she’s doing.

At this point, the thought that this is just a mugging or robbery never enters my mind. This is more sinister. A staged breakdown to lure us in, a rehearsed plan, disabling our means of evacuation, and the display of deadly weapons are indicators that these people wish to kill us at worst, or take us hostage at best. My decision would be to counter deadly force with deadly force.

I now have two armed threats to address. One is standing in front of me holding a gun; the other is outside my wife’s car door holding a knife. I’m hoping my wife was alert enough to identify the threat, but hope isn’t a strategy, so I must assume she’s unaware of the danger in front of her.

The man shoves me back, which means he’s within contact distance. My response is to use a pinning check to direct his gun offline, grabbing around the slide (or cylinder if it’s a revolver) to prevent the gun from cycling when he fires. As I perform this action, I simultaneously torque my hips in the opposite direction to hollow my body out. This helps get me out of the line of fire while moving my gun side away from the threat and allowing me to draw my pistol.

I engage the threat from a body-index position. Knowing my wife is downrange, I angle my muzzle downward. As I break contact, I move offline toward my vehicle to close the distance between me and the second threat and get a better angle for selective targeting on the first.

I expect at this point that my wife is engaging the woman, using the car door to knock her off balance. As I address the female assailant, I assess her response. Has she lost her will to fight? Do I need to scale down my level of force? What comes next will depend on her.

Once the situation is under control, I check myself for holes, check my wife, and render medical aid as necessary. I also take this time to re-kit in case these two weren’t working alone. I have my wife call 911 if she can get a signal. If not, we’ll have to rely on a Good Samaritan of our own to contact the authorities and relay our location.

Never take things at face value. When approaching any situation, ask yourself: What’s the most likely scenario, and what’s the most dangerous scenario? Then, look for baseline anomalies in human behavior. Following this approach will put you in a proactive state where you can make sound decisions before SHTF and quick decisions when it does.

Survival Expert Tim MacWelch’s Approach

Preparation

One of the most common Biblical concepts to seep into pop culture is the story of the Good Samaritan. Most people understand what a Good Samaritan does, but not everybody knows the original story and context. This tale was first told by Jesus and is included in the Bible in the Gospel of Luke. In short, two supposedly righteous men pass right by a traveler who was beaten, naked, and left for dead on the roadside. A third man comes along, the Samaritan (a follower from different branch of Judaism, who didn’t get along with people of the local faith), who helps the poor man. The meaning of the story is that we should help those in need, regardless of our personal differences and preconceived notions. That’s a tall order, but it’s the task we’re handed.

To be a true “Good Samaritan,” we’re asked to intervene in situations that don’t directly affect us. If we fail to act when we could have acted, we may be in more than just a moral or ethical quagmire. We may be going against our very faith. And if you do decide to help, many countries have “Good Samaritan Laws,” which prevent a rescuer from being successfully sued if something went wrong as they attempted to help a victim. So in at least one respect, both religious and legal doctrines are in favor of us trying to help those in distress.

Now, let’s define “help” in its different forms. There are some ways to help someone in legitimate need without putting yourself at much risk. For example, I’d consider calling a tow truck for this hypothetical young couple, once we reach an area with mobile signal. I might even pay for it, if I was feeling particularly generous. And I wouldn’t hesitate to notify local law enforcement, once we reach an area with signal. Everyone should have the non-emergency number for their local law enforcement in their wallet. All of this calling can be done without interacting with the people in question, but maybe that’s not the kind of help they needed? Time may be an issue. Maybe one of the stranded motorists needed medical help (which I’m trained and equipped to provide, and you should be too). Someone could die in the time it’d take for you to find phone signal, explain the situation and location to the authorities, and for the first responders to get on the scene. The kind of help they need may only be served in person, and it may be needed now — later may be too late.

So before I pulled over to offer assistance, my first consideration would be whether I’m ready, willing, and able to help. On any given day, I carry a four-way tire iron, a small air compressor, jumper cables, a serious first-aid kit, flares, road triangles, and many other things to help myself and those in need. And if I’m ready, willing, and able to help, then my next question would be whether it’s safe to help or not. If cars are whizzing by on the highway, am I likely to get hit by stopping and getting out of my vehicle? If there isn’t a soul on the road, am I about to be in some real-life horror movie? These things would certainly be in my head.

I could mitigate the traffic threat by pulling as far off the busy highway as possible (without getting stuck in a ditch) and using the vehicle hazard flashers, flares, and reflective signs to reduce the risk of someone plowing into me at 70 mph. Or on the dark and lonesome highway, I could look at the people and the surroundings as I drove by slowly, then circle back if they looked legit (and after notifying the local PD or sheriff’s department). We could even pull up beside them and talk through the glass (without fully rolling down the windows or unlocking the doors). Ultimately, I’d have to trust my situational awareness.

In your preparation for scenarios like this, you should take the time to study the legal means of self-defense in your locality. If concealed carry of a firearm is legal in your area, take the time to get a permit (if necessary) and train frequently. Practice drawing it from concealment while standing, while holding a flashlight, and even while seated. Keep practicing to improve your ability to draw quickly. Mix it up by practicing some support-hand flashlight strikes, then drawing your CCW. And since darkness follows day like clockwork, consider adding a tactical light to your handgun.

Our final consideration for preparation is gear. Aside from your normal vehicle tools, first-aid supplies and other vehicular preparedness gear (like food, water, space blankets, etc.), you’ll want to have a quality flashlight. There’s nothing wrong with carrying a big Maglite. Stuffed with four C-cell batteries, it’s both a flashlight and a formidable baton for striking. Or you could go with a high-intensity tactical light to blind a potential adversary. Look for one that has crenellations (square teeth). These allow the impact of a small flashlight to deliver pain like a hit from a larger, heavier flashlight.

On Site

Continuing with our scenario, if I decided to help this forlorn and out-of-place couple, my first action is to park in the safest spot. As the location allows, I’d park behind the stranded car and create a good space between my vehicle and theirs, at least three car lengths. I’d also put our vehicle on the road shoulder, but without risking a loss of mobility or control in a ditch, mud, wet grass, or loose gravel. In short, we’d look before we park. I would then turn the dome light off, so it didn’t come on when the vehicle doors open. This would keep any bad guys from knowing the number or location of the people in my vehicle.

If possible, I’d have my spouse move into the driver seat, without getting out of the vehicle. In any case, I’d want them in the driver seat with the engine running, windows up, and the doors locked. My spouse would then be my “overwatch” for this roadside rescue. From the rear position, my spouse would be able to keep an eye on things at the broken-down vehicle, as well as behind our vehicle and to the sides of it. I’d leave my spouse with instructions to do three quick taps on the horn or flash the high beams three times if anything seems out of the ordinary, and to stay in the car no matter what happens. Before leaving I’d remind them of my love, and I’d remind them that our vehicle is a 1-ton weapon, easily capable of running over bad guys. They need to be mentally and physically ready to drive the vehicle into a person or the other vehicle, if things take a bad turn.

Approaching the stranded car, I certainly don’t want to look like a predator myself, especially if the young couple needs legitimate help. For example, I wouldn’t approach the scene with my gun drawn. I’d keep the flashlight in my left hand (to free up my dominant firing hand) and watch the motorist’s hands and body language. I’d also keep an eye out for any bulges under his clothing that might indicate a hidden weapon. I’d try to keep the strangers in sight, if possible, and not let them get in between me and my vehicle. We don’t need to be shy if things start to feel wrong. It’s OK to tell them flat-out to stay where you can see them and to find out more about them. It’s more important to be safe than to worry about being rude.

Not being a mechanic, I probably wouldn’t be able to mechanically assess a vehicle on the roadside (especially in the dark), so it would be hard to determine whether the “breakdown” was deliberately staged. I’d just have to watch the people, study their demeanor, and listen for holes in their story.

Crisis

There’s a gun in my face. It should never have gotten this far, but as the threat emerges in this situation, I’m not going to comply or become a victim — I’ll defend myself, even if it’s through lethal force. There’s no compliance here. Why not? Because there’s a big difference between a crime of opportunity (like mugging people for wallets and purses, or carjacking random motorists) versus this deliberately staged ambush. Sketchy mister motorist and his skid row princess probably aren’t planning to carjack us since she just slashed two of my tires. So maybe they just want our money, or maybe their friends are hiding in the bushes and they’re going to chop us up for black-market organs. We don’t know, and I’m not going to find out.

If my spouse saw my hands go up, I’d hope to receive a useful distraction (like horn honking or light flashing). But I could make my own distraction too. I’d just need to say something like “Wow, your bitch just got stabbed with her own knife!” In the two seconds he looked away, I’d draw my weapon and fire. Then, I’d check my surroundings, and kick the revolver away from the fallen man. After locating the woman and engaging her, I’d demand that she drop the knife. Compliance equals life for her. Moving into the roadway a little for better visibility, I’d back toward my own vehicle (to avoid being blinded by my own headlights), and I’d check on my spouse (without taking my eyes off the woman).

Now it’s time for the long and messy wrap-up. Without mobile phone signal, and with our vehicle disabled, we’d have to take their car (if it worked) or drive on two flats. But so many questions arise. Do I render first aid to the man that I shot in self-defense? If I didn’t have to shoot the woman, do I use some kind of restraints on her? Do I stuff her in the trunk of one of the cars? If there’s an escape latch inside the trunk, that’s a useless method to confine her. It may also cross a legal line that changes our situation. The local laws may side with her for unlawful imprisonment if she’s locked in a vehicle. As I said, it’s a mess.

Most likely, we’d have to leave the scene of a crime to get help. By heading toward the nearest town and watching our phones along the way for a signal, we’d call 911 when we could and inform law enforcement. We’d use GPS, intersections, road mile markers, or the length of time traveled to convey the location to the authorities. Finally, we could head toward the nearest police station or sheriff department to explain what happened and make our statements.

Conclusion

We’ve all seen broken-down cars on the roadside, and most us have probably been stranded by a disabled car at some point ourselves. Being stranded is part of our mobile lifestyle. And while more than 99 percent of distressed motorists are truly in need, bad guys feigning the need for help alongside a highway is as old as the concept of the highway itself. Unfortunately, we don’t often hear about motorists and hitchhikers being lured into traps and ultimately robbed, raped, or murdered as front-page news until it reaches pathological, serial killer status. Do a few web searches for stranded motorists being kidnapped or killed, and you’ll see it happens more frequently than you might think.

From the earliest days of these thoroughfares, “highwaymen” or “road agents” robbed travelers in remote areas and then disappeared with the loot. Little has changed over the centuries, and although very rare, it still takes place today. Roads can provide a natural funnel, directing the unsuspecting quarry right into a trap. Add the bait of the “poor young couple” to the trap, and it’s a damn-near-irresistible ploy to catch a soft-hearted do-gooder. And while we’re not suggesting you avoid helping beleaguered motorists ever again, we can remind you that there are many ways to help. You don’t need to stop on that dark and lonely road. You can simply call the local police non-emergency line. They can check it out and offer help if it’s truly needed, and you’ve still done your good deed to render assistance.

Meet Our Panel

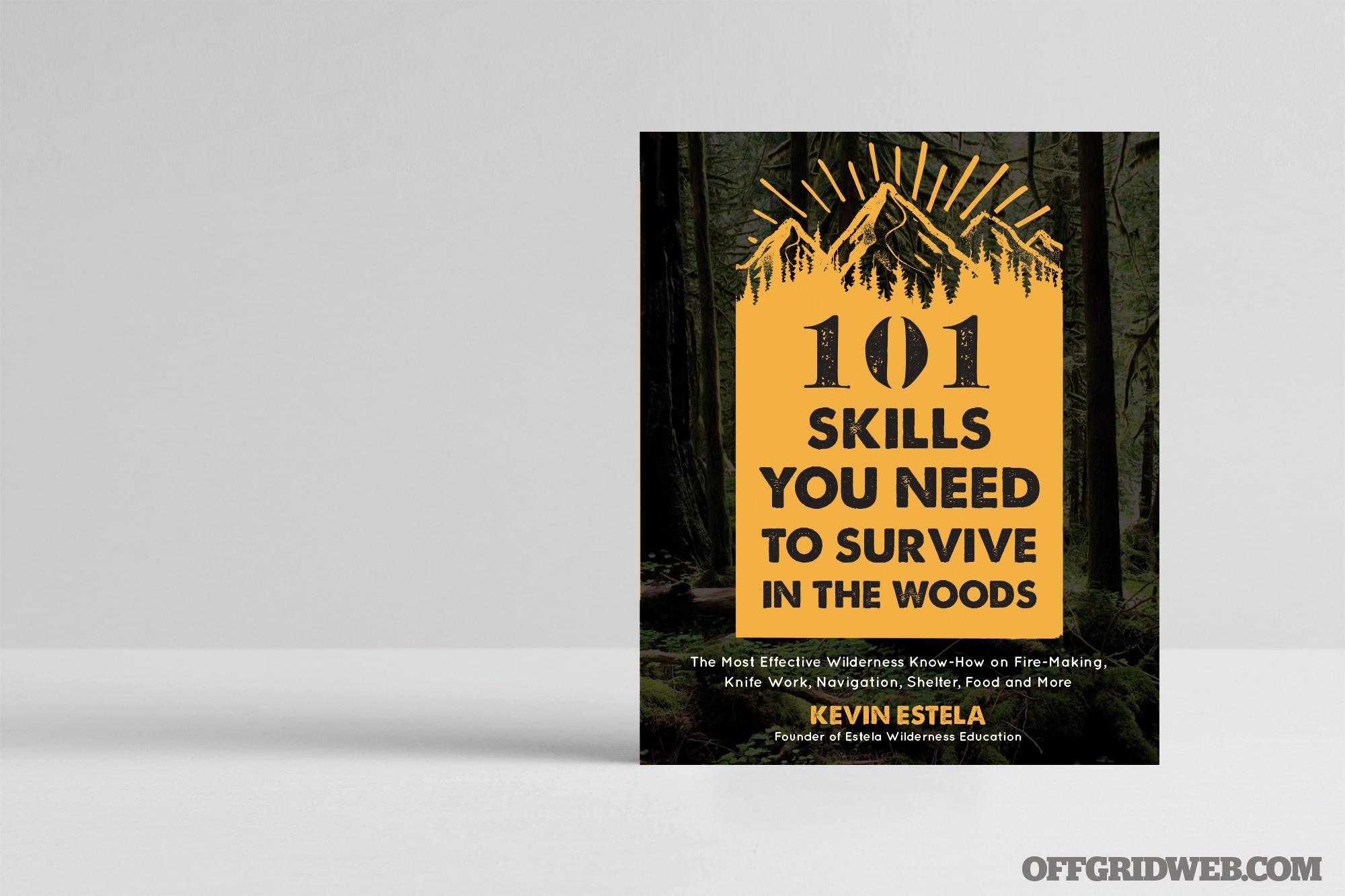

Tim MacWelch

Tim MacWelch

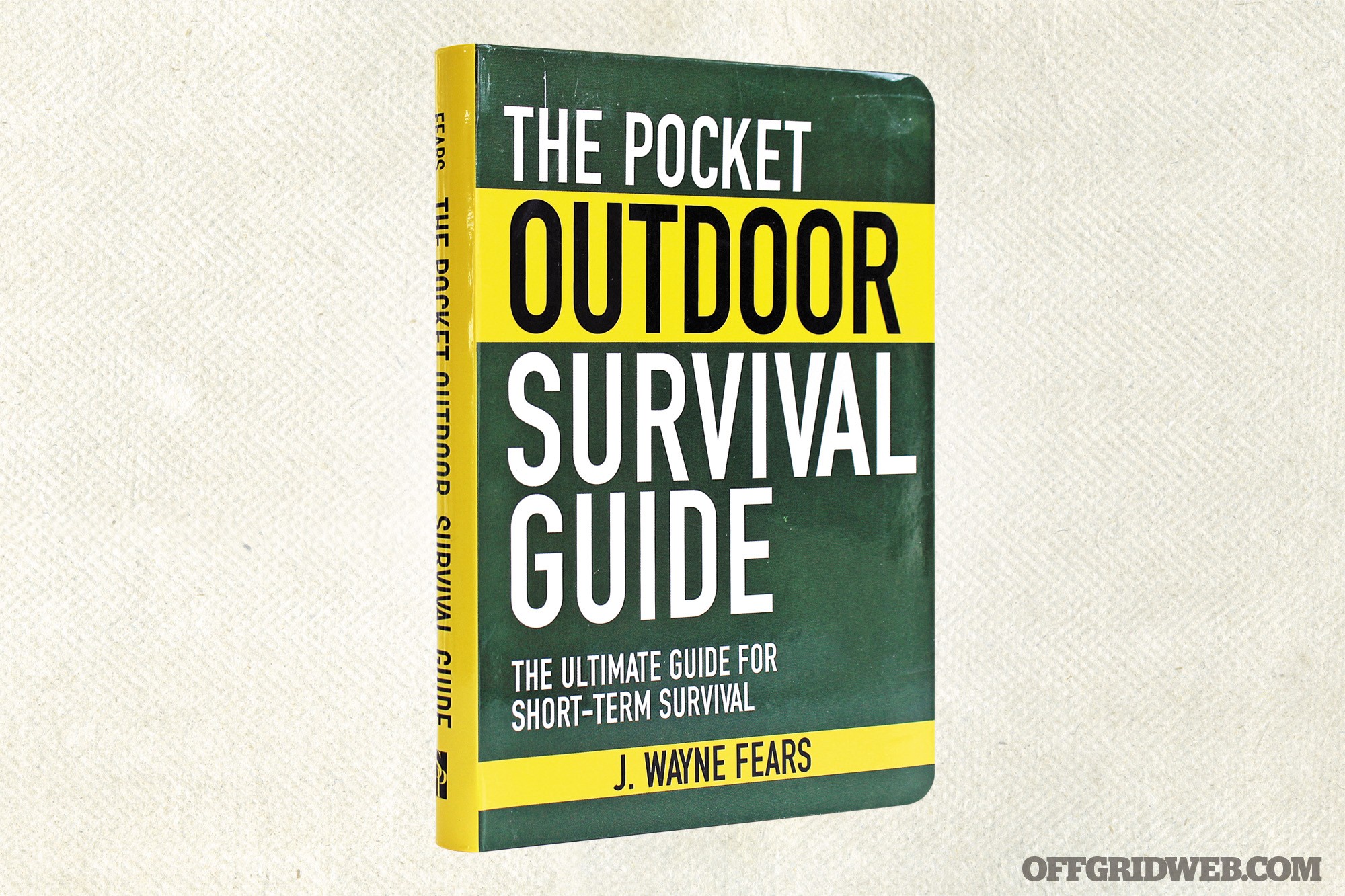

Tim MacWelch has been a survival instructor for more than 20 years, training people from all walks of life, including members from all branches of the U.S. Armed Forces, the State Department, DOD, and DOJ personnel. He’s a frequent public speaker for preparedness groups and events. He’s also the author of three New York Times-bestselling survival books, and the new Ultimate Bushcraft Survival Manual. When he’s not teaching survival or writing about it, MacWelch lives a self-reliant lifestyle with his family in Virginia. Check out his wide range of hands-on training courses that are open to the public at www.advancedsurvivaltraining.com.

Chad McBroom

Chad McBroom

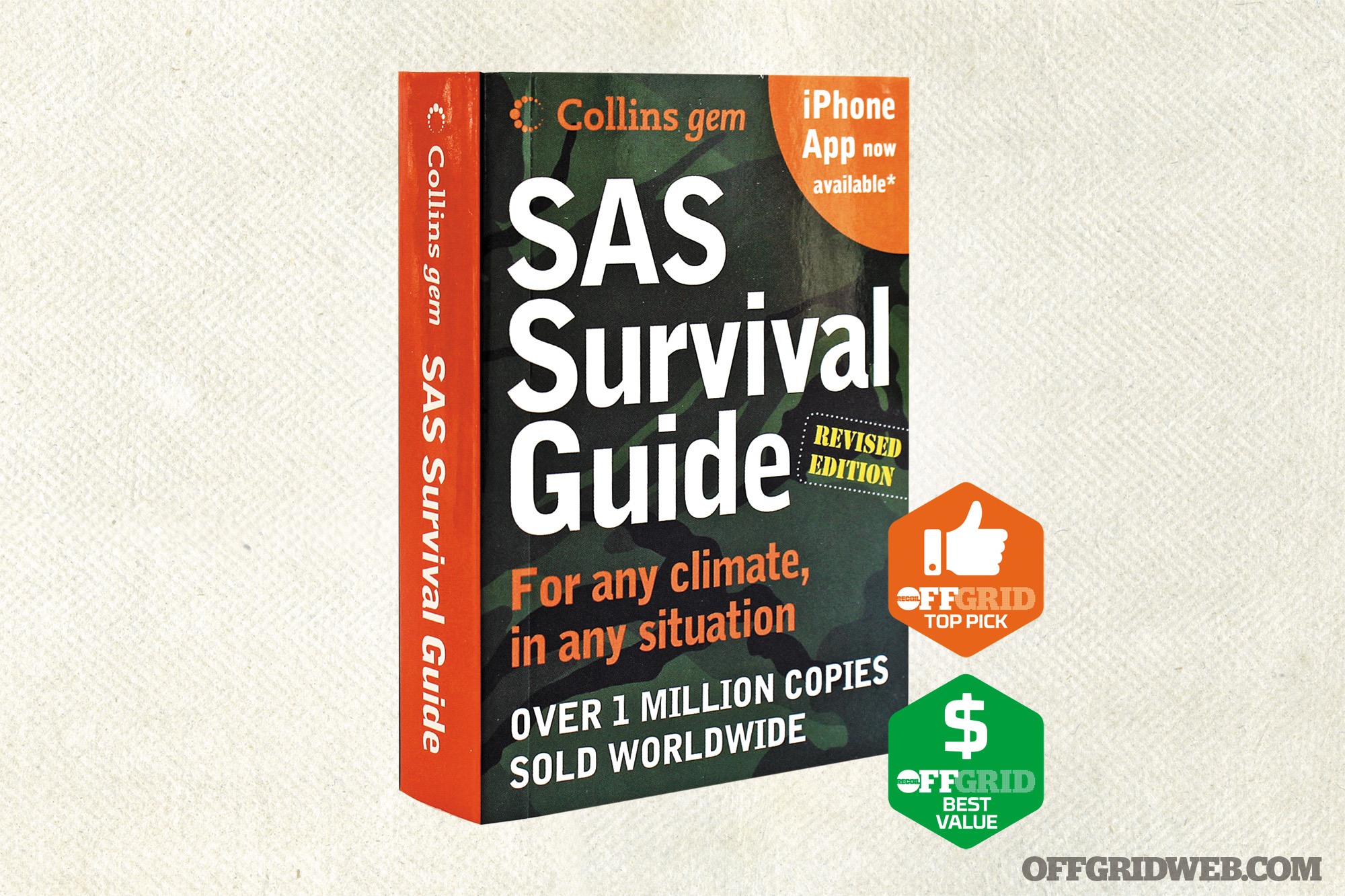

Chad McBroom is a 22-year veteran law enforcement officer with most of his time spent in the tactical unit. He has spent over 30 years studying various combative systems and focuses on the science of close combat. Chad is the owner of Comprehensive Fighting Systems, offering training in empty-hand tactics, edged weapons, impact weapons, and firearms tactics. He’s also a regular contributor to RECOIL. Check out more at comprehensivefightingsystems.com

Tim MacWelch

Tim MacWelch Chad McBroom

Chad McBroom